I visited old Lucknow in February 2014, three months after a visit to Iran to comprehend how Shia Islam brought from Persia in the 1700s found a permanent home in the fertile soil of Lucknow, and for hundreds of kilometers around. Shia Islam here was Iranian in its source and inspiration, but it assimilated and became Hindustani in practice – in language, music, food, clothes and references. There was an ‘inter-being’ that took place with the Hindu religions of the area, a two way osmosis that generated an assimilated way of life; a merging along the borders of cultures that brought into being the comfort of what is there today. This mixing of cultural currents is the essence of India, the source of our pluralism. There are differences, vexed and vicious ones that grow each year, but the connections remain.

The uniformity of ‘Muslims’ in India is taken for granted by all of us when in reality they are torn asunder (like the rest of Indian society) by divisions of sect, region and culture. In Lucknow, the Shia – Sunni divide is significant to have caused serious riots over many occasions and even today there is enough tension during the month of Muharram when the Shia’s ritually curse the 3 Caliphs preceding the fourth Caliph and the Shia founder Hazrat Ali. The Iranians constructed a culturally uniform (98% Twelver Shia) nation over these 300 years, while Indian Muslims continue to struggle with the Shia Sunni divide – they passed this tension to Pakistan, Iraq and Syria. (A learned article “The Lucknow Connection” by Khaled Ahmed)

Pehle Aap. The Persianized culture of Lucknow 70 years ago was much gentler than it is now; even today interactions with the citizens of Lucknow on the street are a pleasant departure from the rough and tumble of khari boli of Delhi. However, the landed elite of Lucknow were out of touch with revolutionary reality and found themselves swept away by the forces of democracy. Freedom from the British, the increased use of Hindi and Devanagari in government after 1937, partition of the country in 1947, and the active support by the landed Muslim class of this division meant a debilitating reduction of this Shia-dominated culture. In addition, the 1950 abolition of landlordism and the resultant elimination of their income impacted the Nawab families catastrophically; an event they did not foresee and were not able to adjust to even much after it took place.

Satyajit Ray’s classic Shatranj Ke Khilari filmed in 1977 is symbolic of the detached ruling Nawabi class; though set in 1857 it brilliantly showcases the lifestyle of the rich, landed class immune to the forces of history; children engrossed in a game to the exclusion of real life while momentous events overtake them.

My grandfather was a member of the Indian National Congress till 1967, and was an integral part of the idealistic impulse for democracy during and after freedom from the British. Ironically, he was singularly responsible as a minister for the U.P. land reforms in 1950 that swept away the landlords and gave ownership rights to peasants who tilled the land. The old land order was destroyed, but Independence also brought neglect to much of the heritage that had been built and patronized by wealthy Nawabs and Taluqdars.

Their sources of revenue eliminated, the Nawabs and their royal patronage withered away quickly; the rough-hewn peasant culture slowly enveloped the city. Lucknow became a magnet for people from all over Uttar Pradesh, and millions of migrants found succor and employment in this city and changed its culture irretrievably. The city of 500,000 in 1947 is now 3 million, and an absence of urban planning has ensured that city life has gone from bad to worst. In a sense, not much has changed from 1799, when British visitor William Tennant remarked on the brilliant buildings in Lucknow which had no equal in Britain; and he equally noticed the city’s “great poverty and filth”.

How much can one complain about a desperately poor nation not protecting beauty and heritage when most citizens go hungry and utterly dispossessed? As in the rest of the country, the relentless forces of history and the march of democracy have devastated Lucknow’s built heritage. This was uppermost in my mind as I walked around seeing the crumbling buildings of the old order, and the degrading poverty of old Lucknow. Some individuals and Waqfs have ‘restored’ some buildings, leaving them standing stronger but certainly worse off aesthetically than before. Today, with so much more wealth available with the State, we must find a balance between schemes for the people and for allocating capital to protect our heritage, the government must work with civic society to save what is left. Sentiments like mine have been expressed before, I wonder if anything will change – but there is no other way other than for the State to become more resolute in its actions in this area.

The old Lucknow I walked through in February 2014 was an extended slum - excruciatingly filthy, bereft of civic services or urban planning, overwhelmed by population, terribly poverty stricken, with it’s built heritage buried under garbage and filth. No different from any city in Uttar Pradesh, where the Aam Aadmi lives forgotten by government and by modern civilization. The residential parts of Lucknow where the politicians and bureaucrats stay is, needless to say, relatively outstanding - a common feature of our capital cities as anyone from Delhi or Mumbai or Bangalore or Hyderabad will certify.

For comparison, the Iran I visited in late 2013 had clean cities; its architecture was stunning, superlative and well maintained; amazing urban infrastructure; very Islamic and Shia – and very proud of its heritage, including the ancient pre-Islamic Persian period.

The old parts of Lucknow were constructed from the late 1700s by a religious Shia ruling class; with great care and detail and no expense spared. Each of the tombs of the Shia Imams were reconstructed in Lucknow over time, from Shah Najaf (in Iraq, where Hazrat Ali is buried) to Karbala (also in Iraq, where his son Imam Hussain is buried). Imambaras (reported to be 2,000 large and 6,000 small in the early 1800s) in every locality come alive every year during the Islamic month of Moharram when the martyrdom of Imam Hussain at the battle of Karbala is mourned by the Shia faithful. Masjids, Baradaris and Havelis of the wealthy were constructed all over the city, and a flowering of architecture took place that produced outstandingly beautiful structures that yet have the power to entrance you. Sunnis and Hindus both participated in large numbers in the Moharram processions and in the mourning rites for Imam Hussain, who was the ‘patron saint’ of Lucknow. Shi’ism crossed boundaries of religion, as the martyrdom of Imam Hussain (the grandson of the Prophet), his story of life and death, and his righteousness fighting the much stronger forces of injustice (the Ummayad Sunni Caliph Yazid) captured the fevered minds of the landed, merchant and migrant labor alike.

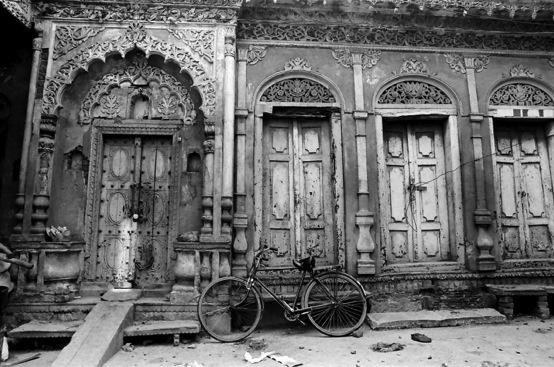

Private homes, public heritage. Lucknow’s architectural heritage has been destroyed not just by a lack of will by an uncaring bureaucracy and political class, but also by uncontrolled construction and an absence of zoning laws and supervision by municipal authorities to ensure heritage buildings are maintained or restored to a defined standard. The old Lucknow families and the more recent immigrants I met expressed a deep sense of loss of a great past, and while all derided the current state of affairs, they all were disconnected from their heritage as getting along with life today was a burden big enough to forget everything else. I saw no effort from the government towards restoration or slowing down the disappearance of heritage buildings; in the Nakkhas area my young guide Atif showed me one intricately carved balconies that was all that are left of the scores of former courtesan homes each of which had a similarly artistic façade till 5 years back. Heritage private properties are being torn down as fast as possible to make the ubiquitous and faceless city floors common across India – there is no law against urban ugliness.

All the monuments were constructed of burnt brick covered by a layer of finely worked limestone and mud mixture, and this material is mostly breaking down. Unlike Delhi, Agra and Jaipur where royalty built cities of stone, Lucknow did not have a significant source of stone within transport distance or one politically in their control. The work on the limestone-based plaster is absolutely stunning, it looks like stone from a distance, but time is of necessity unkind to this master craftsmanship.

The ASI managed Residency is extremely well kept, authentically maintained to what it was after the fierce battles fought here during the first war of Indian independence in 1847. The Waqf managed properties on the main tourist route are however in a mess, with arbitrary restoration deploying cement without thought, and bright plastic emulsion colors without an aesthetic combination or need. The internecine politics in the Waqfs are debilitating to any kind of progress, and representative of the sad state of affairs in the Muslim community across India. Religion intrudes in protecting heritage, and the secular State retreats.

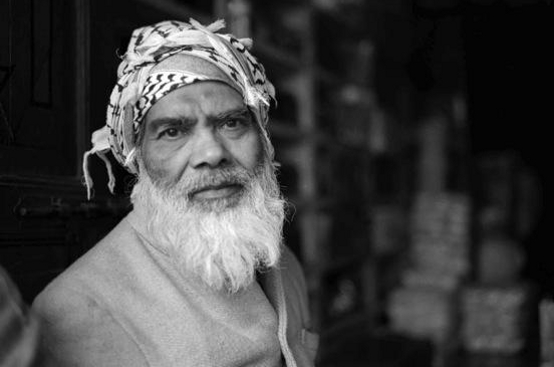

Memories. The architectural beauty and intricate designs of the scores of Imambaras, Masjids, and Shia shrines visited; the wonderfully sounding Rifa-e-Aam club now crumbling and controlled by the aging Panditji (was he really a caretaker appointed by the Raja, or is he just a squatter?) along with his gun toting mafia; the afternoon spent with a Kabootarbaaz on his terrace calling his pigeons to return home in coordinated flight and hoping to bring those of his competitors; the positive energy of the dirt poor immigrant families settled in single room hovels by the Bara Imambara studying for a better life in the schools we all deprecate but which is their only ticket to a better life; the gentle Atif who took me from sunrise to sunset to the hidden streets of Nakkhas and Chowk to places created by the Shia from their collective memories of the holy land of Iraq; the amazing street food vegetarian thought I am; and the atmospheric small towns of Kakori and Dewa Sharif.

Old Lucknow is overwhelmed by population, poverty and administrative apathy, and remains a crumbling edifice of singularly beautiful public monuments and stately private homes that came about by a rare synthesis of civilizations. Yet all is not lost as the intangible heritage of Lucknow continues to run through the veins of all of us from Uttar Pradesh born Hindu, Shia or Sunni. This syncretic tradition is under renewed attack by religious purists and clergy from all sides, but it endures as it must to enable us continue to claim Imam Hussain as a metaphor of the struggle by the forces of truth and justice against the (always stronger) forces of injustice and exploitation; in life, and in death.

Early morning at the Bara Imambara

The Shia families along the walls are settled illegally by a Shia Waqf leader as vote banks. I was heartened to witness the vitality of bright-eyed children going to free government schools; and the desire of parents to improve their future. A teenage girl copies Noha's : songs in Urdu in memory of the martyred Imams; as her mother goes about her daily chores.

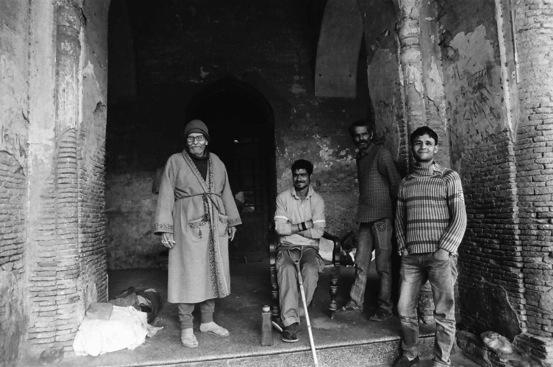

At the Rifa-e-Aam ‘club’ established by the then raja of Mahmudabad in 1860. Panditji, standing on extreme left, was the caretaker 50 years ago and remains there today having taken over the club by the help of his thuggish son Patrakar Pandey.

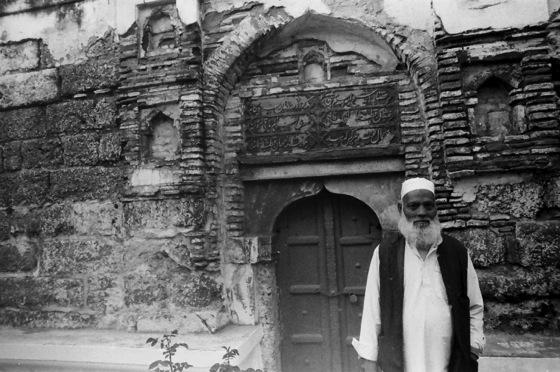

‘Nadan Mahal’, where Ibrahim Chisti the brother of Khwaja Gharib Nawaz is said to be buried here. The Khadim and Imam of the nearby Jama masjid stands in front.

Early morning at the Talkatora Imambara and Karbala burial bround. Thakur Narayan Singh is the chowkidar here since the last 40 years. He finds sukoon here, and goes to the Rauza when he is unwell. No doctor for him.

The Yatimkhana (orphanage) constructed 1912 by local Taluqdar families, the raja of Mahmudabad, and wealthy Khoja Muslims from Mumbai. In the foreground is the SUV of the Chairman of the Waqf that runs the orphanage.

The Rauza Hazrat Abbas (a companion of Imam Hussein, both martyred at the Battle of Karbala). Crowded by the faithful, it has a steady stream of women seeking emancipation from their worries about their children.

Imambara Mughal Sahiba with stunning work on the façade. Shanu (the caretaker from the Waqf) is helpless at its fate as there are no funds for its upkeep. The ceiling had fallen in many places, and sullen looking masons were undertaking shoddy and thoughtless cement based patch-up work.

Katari Tola haveli, one of the few whose façade is yet intact in the sad way it is.

Tehsin Ki Masjid, recently restored with cement most probably with money from the Gulf.

Shah Najaf grounds, on the banks of the Gomti. The swans in the background complete the picture of an abandoned Ambassador car, a symbol of decay amidst beauty.

Tile Wali Masjid : The vibrant Madarsah around it was destroyed by the British after 1857, and the grounds cleared of possible ‘mutineers’.

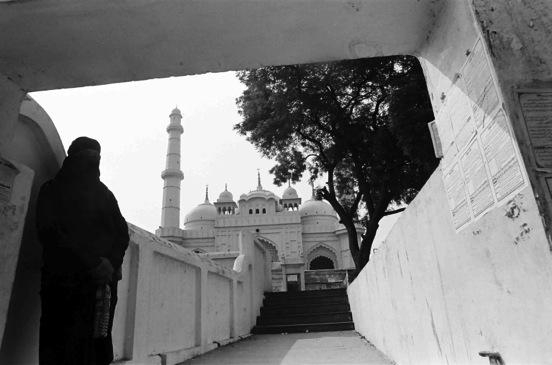

Early morning at the former British Residency, wonderfully maintained today by the Archeological Survey of India. A burqa clad woman works out in the distance, amidst the ruins of our colonial rulers.

At the Residency, brooding memorials to the British soldiers, women, and children who were killed by soldiers of the British Indian army in a mutually brutal war in 1857. The first war of Indian independence.

At the British Residency, brooding memorials to the British soldiers, women, and children.

Shia Madarsa Sultan ul Madaris. No infrastructure, no equipment, no books – just aimless youth taken off the roads to pursue studies of some manner.

Maulana Farid ul Hasan, the Principal of Madrasah Nazmiya Arabic College on the left. His great grandfather founded this early last century after migrating from Amroha (another Shia center in Western UP; also the ancestral home of my wife’s family); and his father remains a prominent Shia leader in Lucknow.

The Hazrat Shah Turab Ali Kalandar shrine, at Kakori 26 kms outside Lucknow.

Hazrat Shah Turab Ali Kalandar shrineHazrat Shah Turab Ali Kalandar shrine

Hazrat Shah Turab Ali Kalandar shrineHazrat Shah Turab Ali Kalandar shrineHazrat Shah Turab Ali Kalandar shrine

Hazrat Shah Turab Ali Kalandar shrineHazrat Shah Turab Ali Kalandar shrine

Hazrat Shah Turab Ali Kalandar shrineHazrat Shah Turab Ali Kalandar shrineHazrat Shah Turab Ali Kalandar shrine

Bhulbhuliyan corridor on the rooftop of the Bara Imambara.

Migrant mother and daughter live on the grounds of the Tile Wala Masjid.

Migrant mother and daughter on the grounds of the Tile Wala Masjid

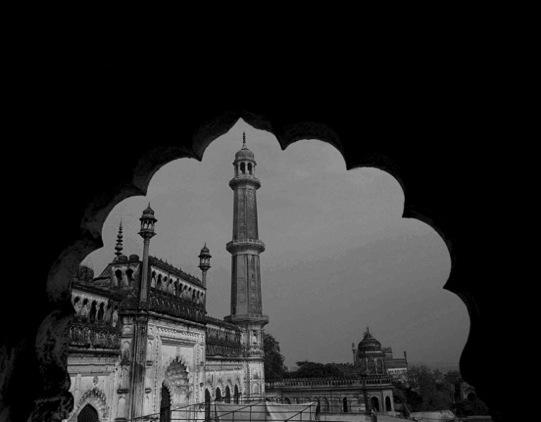

Bara Imambara at Sunset

Asafi Masjid, next to Bara Imambara.

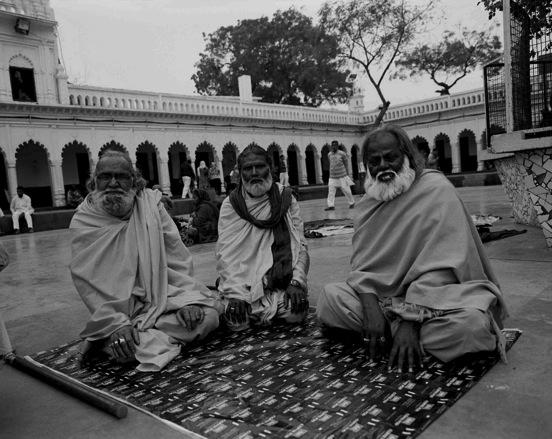

At Dewa Sharif, 19 kms from Lucknow, is the Warsi Silsila of Haji Waris Ali Shah. The murids of the Pir dress in geru.