Kashmir Portraits

Mass tourism to a favoured destination by the newly empowered middle classes is a sustained and coordinated assault by these agents of modernity and consumerism on the culture of the locals and on the environment, till such time only a vague memory is left of what once was. Youth specially ignore this change, immersed as they are in the new by their energy, without knowledge of their real loss; by the time they realize it, it is usually too late.

Some places, with languorous beaches and placid weather or scenic mountains and cool valleys, viscerally grab the attention of the tourist class; desultory visitors with little commitment towards the locals; or even an understanding of the light touch, quietude, listening, or observing. Tourists who consider themselves sensitive too are a part of this assault on the local culture. Ask a thinking Goan how burgeoning domestic tourism over the last decade has overwhelmed their limited infrastructure, destroyed pristine beaches, cut down decades old trees to expand main roads, splayed an unprecedented quantity of consumer plastic on hill sides, and created traffic chaos on narrow village roads; how tens of thousands of Indians from other states and other nationalities have settled down in what was once a languid backwaters with a certain pace of life. Goa is now overcome by commerce that compromises even the wealthy who financially benefitted the most from mining, construction, hotels, restaurants and taxi services. A better standards of living for many Goans is accompanied by a deep sense of loss, which is much more than simply nostalgia for their past.

The Goan story of unbridled mass tourism and wrenching cultural dislocations is being replayed thousands of times over our rapidly shrinking country, and across the world. Kashmir, ironically, has (mostly) kept these disruptive cultural forces of commerce and consumerism at bay only due to the extended decades of often-violent political unrest. This volatile political situation goes through phases of ‘normalcy’ and ‘militancy’, and organised tourism continues to mark time due to inadequate infrastructure outside the Srinagar, Gulmarg, Pahalgam circuits. Big private capital deeply dislikes uncertainty, and has not yet established a collaboration with modernity and ‘development’ in Kashmir. I wonder what we should wish on the Kashmiri's.

Kashmir, unlike any other region within the three successor states of British India, is specially burdened with the political complexity of the Partition of India and the communal Hindu-Muslim fires that bedeviled us then; and continues to deepen unbridgeable fault lines. The weak commercial force of mass tourism, an intransigent and aimless Kashmiri nationalism, the powerful influence of a popular Islamic leadership, meddling by the military-religious hands of the Pakistani state, and the shadow of a resurgent Hindu nationalism in India come together with poverty in the villages in a multitude of ways; as I experienced on a visit to the Lolab Valley, 115 kilometers north of Srinagar in May 2016.

Lolab Valley, Kashmir

It was late May, an idyllic rice planting time in Lolab valley; just a month before the killing of the local militant Burhan Wani – a “freedom fighter” for the Kashmiri, and a “terrorist” for the rest of India - that has sent Kashmir and India into a downward spiral out of which neither have come out of as I write this essay in January 2017. It took some thinking to go where few tourists do, but travelling to where real people live real lives was the only way to experience Kashmir and not be dependent on prejudices transferred to me by others.

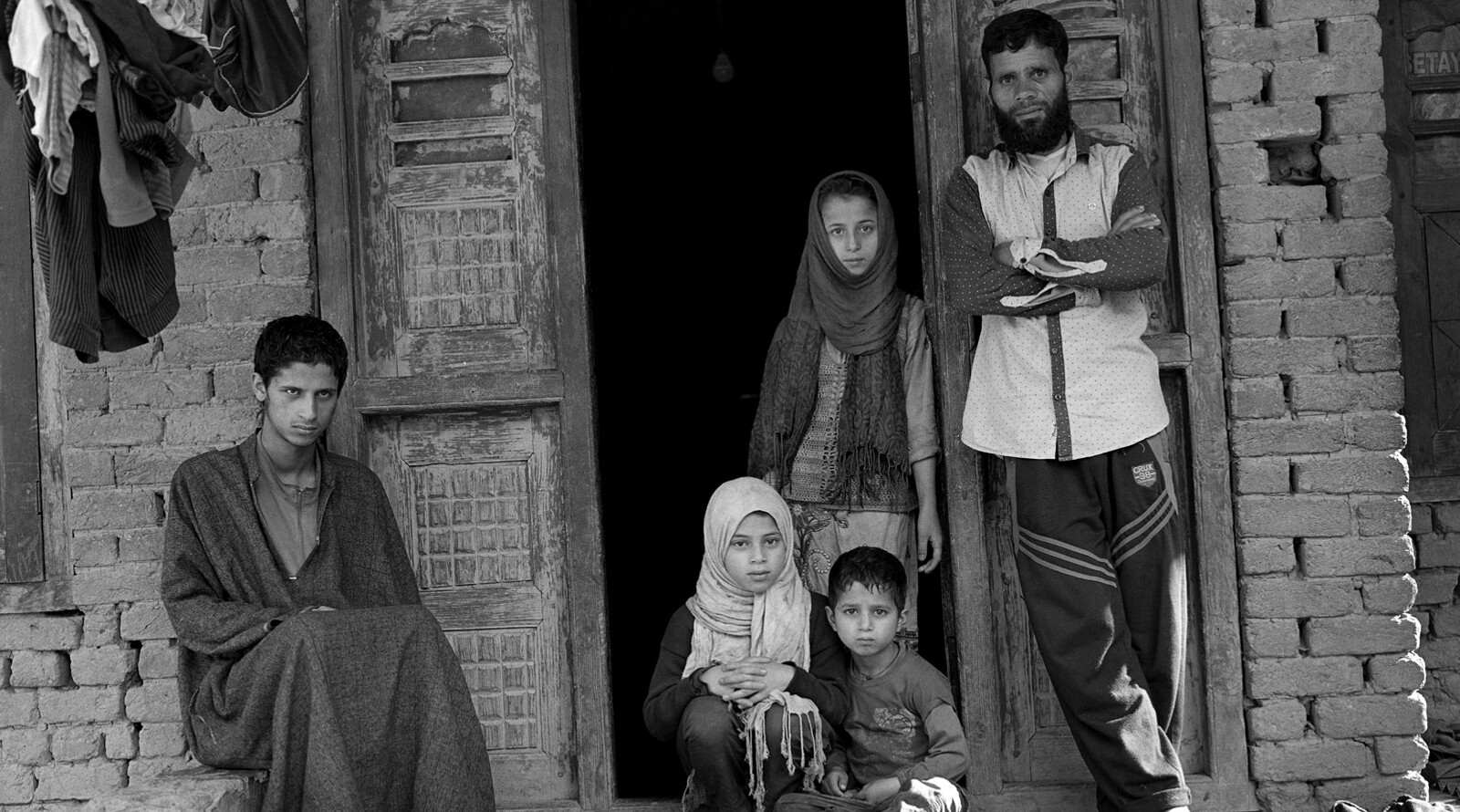

Road to Dardpora, Lolab Valley, Kashmir

My driver and guide, Bashir, is in his early thirties with a gentle and friendly demeanor; like most people I met in my travels. He was, as I realised over the visit, a Hurriyat supporter with deep-seated prejudices about the Indian nation state. He doesn’t think that India is a mostly democratic, mostly peaceful, mostly progressive, caring nation state; quite the opposite, in fact. Gilani is, to him and I suspect all I met, a Kashmiri Gandhi; and the Indian government a force of severe oppression. It was surreal, though, passing through the town of Sopore, the district of Baramulla, and the town of Kupwara whose names one associates only with violence. We passed Vatavan Chogal, with Badam Bagh opposite which Bashir told me, matter-of-factly though I suspect to hide his sadness and anger, is 200 acres of land that once belonged to Afsal Guru. I came face-to-face, fleetingly, with a real person who owned land, not just the enemy of the nation. Now this land was said to be occupied by the Rajwar Tigers, an Indian Army unit.

We drove past an Army painted slogan "मुक़ाम है ख़ुशहाली का, रास्ता है अमन का" – with the words Happiness and Peace jumping out at me. I thought how we all deeply aspire for these, though we are rarely able to even define, much less find them, in this lifetime. Was this slogan, I wondered, directed as a reassurance to tourists that they have come to the right place, to the nervous army jawans seeking comfort in a hostile environment, or to the suspicious locals who find neither in their daily lives? Life looked peaceful enough, though, as we winded our way in between sheep being herded on the tarred road by nomadic Bakarwals.

The Nineties were the peak of ‘militancy’, as the locals refer to it, and even a lower intensity conflict period of the last few years were difficult times for everyday life. The Lolab valley starts at the massive Army camp of Zangli, Kupwara that sits astride the main road, most probably by design to control the entrance to the valley. Bashir told me, looking away from me as if not to hurt my Indian sensibilities, how the massive metal gates (which sit on the road) were shut at 8 pm till 6 am - one just couldn't cross Zangli no matter what the cause or emergency. Another army camp ahead is Duniwari where one just had to get off and walk, and those who the army suspected could be taken in for questioning for days, even weeks. Today, we sailed through without anyone so much as giving a second look, with the army men going about their daily business as in countless bucolic army cantonments across India.

Chandigam

Bashir had booked me at the government tourist guesthouse at Chandigam. It came home to me, over the next week plus I spent here, that the name of this village arose from a distant memory when Kashmiri Pandit families thanked their Goddess Chandi for giving them their Gam in these stunningly beautiful, deeply forested meadows at 7,500 feet. Chandigam, now peopled only by Muslims castes (Pir, Ganai, Choupan, Dar, Lone, Mir, Khan and Sheikh) saw its last Pandit family leave at the height of militancy in 1990s. The shell of a Shiva temple sits on a mountain slope in testimony, mute and evocative, of the fragmentation of the village community and of Kashmiri society. Each time I drove past the abandoned temple, and I did this twice a day, I wondered why the pain of the Pandits hasn’t yet brought redemptive actions by, and catharsis for, the majority community. I suspect the flight of this minority community, small in numbers even when they were resident here, was terribly convenient for those who remained behind. The majority is by definition repressive and contemptuous of any minority, a lesson we have learnt in the aftermath of Partition in India and Pakistan; in the latter, while they freed themselves of control by the Hindus, they created new forms of oppression of their Bangla, Hindu, Christian, Baloch, Shia and Ismaili minorities. The once threatened minority became an oppressive majority.

Himal Warnau, Lolab Valley, Kashmir

We reached the Chandigam guesthouse by late afternoon, to find that the entire place was teeming with hundreds of men waiting upon their local MLA (a minister in the Kashmir cabinet) who had at short notice commandeered the entire guesthouse. There were scores of armored vehicles with heavily armed police all along the road leading to the guest house, and armed security manned the entry gate; I got a full taste of the suspicion that locals face when I was roughly frisked and my bags opened and checked by two scruffy looking policemen with machine guns; till the harried caretaker Munir came running out to vouch for us guide us through. I walked though a gauntlet of curious men lolling around, and not here to do very much other than wait around as is the won't of our sub-continent, who most probably wondered why I was coming to meet their MLA. Food had been cooked for everyone, at government expense I was told later, and I walked over a unique Kashmiri food custom – bones of the meal littered the grounds. These were spread over the guest house corridors too, as well as the carpeted rooms, and everything smelt of biryani and mutton korma for the next couple of days. The washbasin had a couple of towels laying around, though only faintly recognisably as cloth. I somehow slept through that night, in the very room that the apologetic Munir later said the minister had stayed with his band of hangers-on, chewing on and spitting out the bones that I suspect were very much in the carpet yet.

Bashir and I went for a walk outside the guest house, and later to the village while we waited for the minister to leave and the crowd to dissipate, we were welcomed by a farmer who had come with his cow to serve tea for the minister. Fresh milk indeed.

Shalpora Lalpora, Lolab Valley, Kashmir

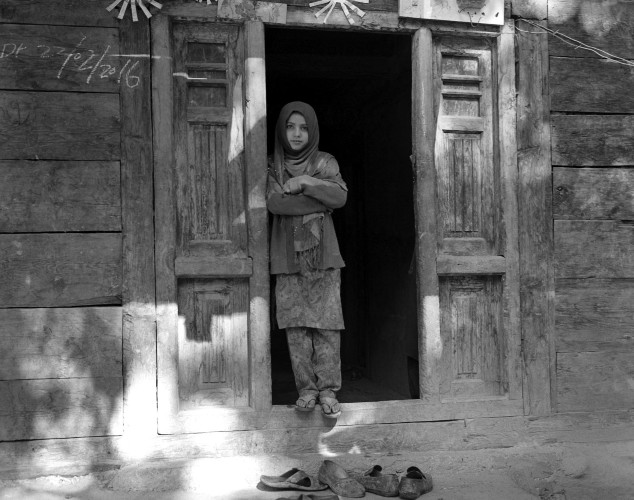

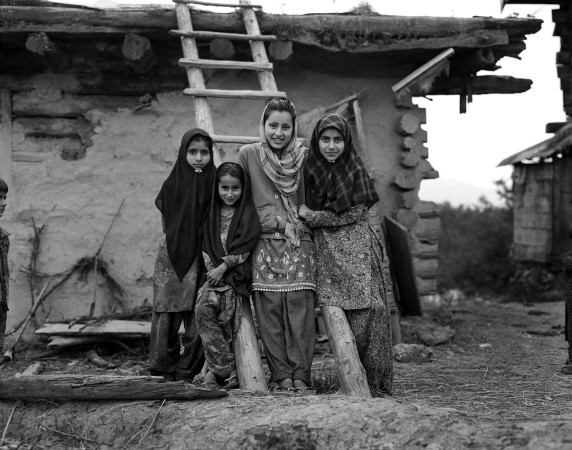

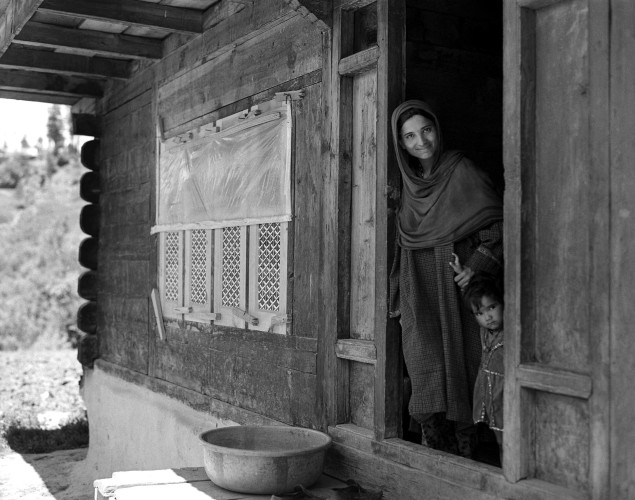

We walked around Chandigam to acclimatize, with Munir’s brother Shabir as our guide. A former madrasa student, Shabir currently managed the lonely chai and provisions stall outside the guesthouse. A stern religious youth, he was not at all in favour of my photographing people. The women and girls especially were indeed shy of the camera, I would be too if someone walked in to my home to photograph. That is an ever-present challenge for a photographer – you are an intruder, despite good intentions, and the best one can be is a sympathetic one. Most people, however, needed only a bit of convincing and engagement to be captured on film: it needed empathy and some relaxed conversations, some banter and at times some laughs.

Poplar grows all around, many planted along the periphery of fields and roads. Curious, I found out that the Australian variety is very fast growing and takes 5 years for full growth, while the local Kashmiri variety takes 10. The government encouraged growing the Australian, as a source of quicker income, but soon realised the downside of playing with nature – the white fluffy seeds it gives causes disease and allergy, and soon it was banned. Government bureaucracy is rarely known to comprehend the long-term consequences of its actions, like the planting of the invasive Prosopis Juliflora in vast parts of arid and semi-arid North India that has overwhelmed local plant life; these decisions are taken for short-term benefit. Now, Kashmiri's struggle with the affects of the ban, which also seems to be flouted with impunity. Just an early example how Kashmir’s lazy, desk-bound bureaucracy creates needless jobs for itself, and causes pain to society.

Kashira Bala, Lolab Valley, Kashmir

I witnessed endemic deprivation and subsistence living, not very different from what one sees across our country in most rural areas distant from a big city, and I became familiar with an evocative Urdu word for poverty: ग़ुरबत. It was used casually, with a sense of sadness and inevitability, and as a summary of life. As I was to witness in the coming days, this continuing poverty without end in sight is a visible marker of how the Kashmiri, and the Indian, state have failed the vast majority of the impoverished people it represents. While certainly representative elections are a critical part of democracy, the absence of effective and quality education, health services, and livelihood in rural Kashmir is an indictment of the capabilities of the elite; and incidentally a mirror of what prevails in India. They let us vote so they can say we did it to ourselves. I held many conversations explaining that the callousness of the state that the Kashmiri’s see in their daily lives is not a conspiracy by Delhi, but is across the vast breadth of rural India. Few believed me.

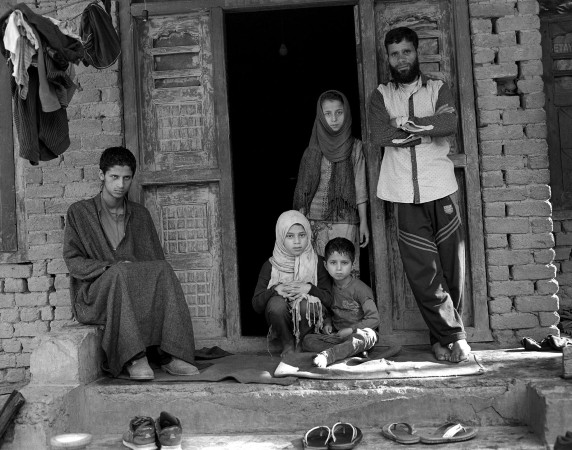

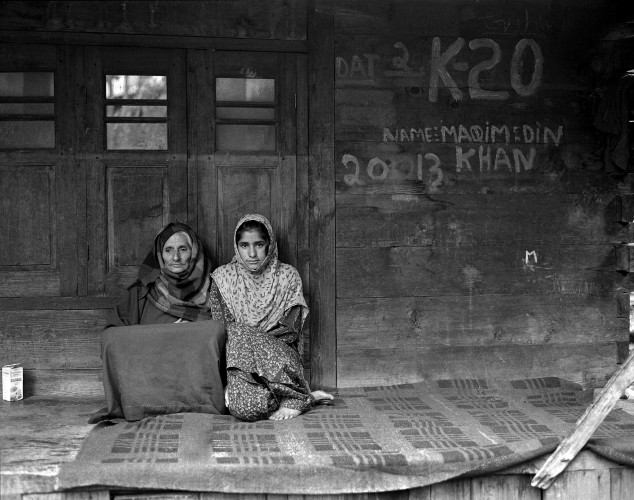

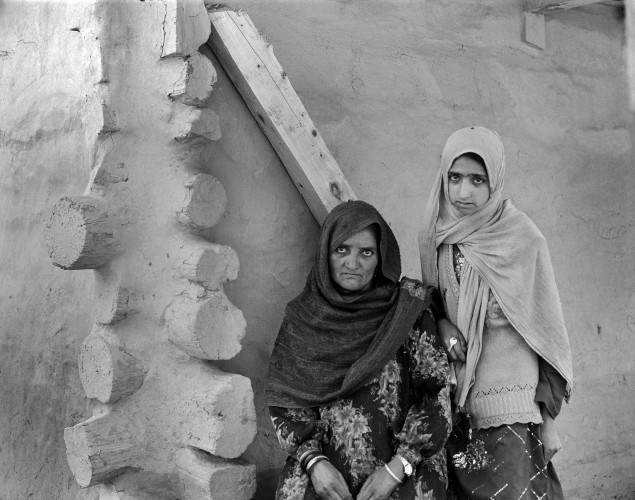

ग़ुरबत के चेहरे, Lolab Valley, Kashmir

Many villagers in Lolab live an organic life in many ways, not out of love for that way of living but because their lives are defined by choices afforded to them by their poverty, and resultant lack of resources. For example, many produce their own fired mud bricks for construction of houses: one brick costs ₹10 if purchased from the market; if you apply your own mud, hard working Bihari labor charge ₹1 per brick; this brick costs ₹3, including the wood required for firing. The entire family is put to work as labor to construct the house with these bricks, alongside expert masons hired from the market. Most construct in fits and starts often shutting down for months on end as construction come to a halt when the money to pay the Bihari’s or the masons runs out, and the family hunkers down for the next round of funds. I saw numerous half-built homes, frozen in time, waiting for the next round of funding.

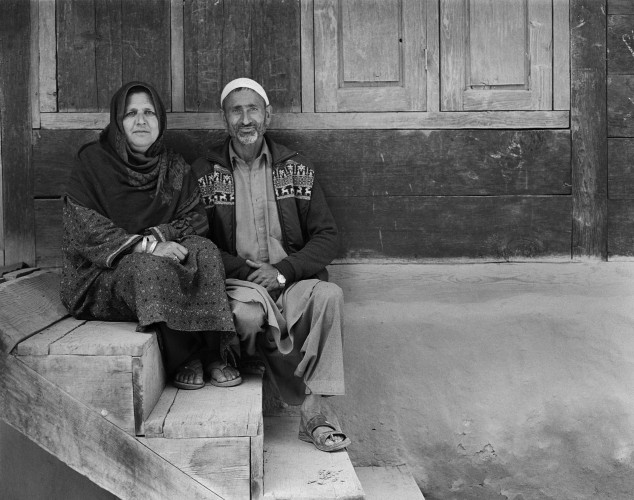

The Kashmiri’s are a handsome people, though I wondered how all the men, and women, are also slim and look fit, even gaunt with attractively sunken cheeks. Poverty and the resultant life of hardship creates a beauty of form few aspire for, but one can appreciate it. Bashir was quick to say, clearly not enamored of city folk, that we can find some overweight people in Srinagar where people do no physical work, and eat meat three times a day. Munir tells me everyone walks a lot on these hilly tracts, and meat and chicken are infrequently eaten, as most people cannot afford these at every meal. “If you are rich, then you eat some meat every meal”. This explained to me the heavy attendance at the local MLA’s meeting, it was after all a biryani meal at government expense.

Munir and Bashir were the cooks, and they had no idea what to make for wheat-eating vegetarian me, and we settled for brown rice and local rajma. Little was I to know that this would be my dinner for the next 9 nights, breaking the monotony with some potatoes in oil a couple of times.

Himal Warnau, Lolab Valley, Kashmir

I realised that for the villager in Bashir, Srinagar is a soulless and amoral place. Women walk around in public without a burkha, there is no feeling of community, life is rushed and only about making money. He would rather stay in his village, but alas his livelihood is in Srinagar and tourism.Bashir says the rains increasingly fail now because the people have forgotten the ways of their ancestors, women walk with their faces uncovered, and in pants and shirt. Because of this shameless modernity, Allah is showing his anger as he did with the floods in 2014. Ouch. I could hear the athiest cringing as the gentle Bashir got more vehement, painting for me the wrath of God coming down on an increasingly godless people. Clearly, he is fertile organic soil for the fiery mullah.

It was cool and peaceful later that evening in the garden of the guest house where I was the sole tourist, and quite surprisingly well appointed with large rooms, clean sheets, big windows facing the forest and surrounded by majestic mountain ranges. The carpet had been cleaned of the vestiges of food, and the smell of the air was Himalayan scented, with mixed pine, deodar, walnut and apple. The evening aazan rang out for 3 minutes from mosques from all sides, so very sonorously, reminding one of the greatness of Allah and of Muhammad being his only prophet. There is really nothing more powerful than an azaan well read by an alim. The silence after the aazan was much deeper in these majestic mountains, and my mind brooded lightly on the timelessness of these two core messages of Islam, as well as on the conflict that people following a religion – any religion - bring to life. If religion was not there, some other equally powerful, totalitarian ideology creates domination and conflict. My dark thoughts were broken by the distant, soothing mooing of a cow, and the more mundane sound of the pressure cooker whistling the dinner rajma.

Kashira Chandigam, Lolab Valley, Kashmir

The Temple

Driving out early morning, I spied up in the mountain what looked like a dilapidated old building; that always gets my photographic interest. Munir, who accompanied us each day as he knew the lay of the land better than Bashir, mumbled it was a Shiva temple destroyed by militants in 2000. There it was, the great divide right in front of me, discovered by accident. Chandigam village once had many Pandit families, who fled in the period of great madness. I came suddenly face-to-face with the villages now dispersed and faceless pandits, a village community ripped apart, with the cross of the flight to be forever carried by their Muslim neighbors and friends. This was the gradual ending of Kashmiriyat, the gentle combination of Sufi Islam and an ancient Hindu heritage in a very religious land.

A couple of hundred feet from the forlorn temple was a small masjid, 60-70 plus years old, constructed in all-wood in the old Kashmiri architectural style, its perimeter protected by a low wooden wall. These two places of worship signaled the relative state of these two major religions in Kashmir today, one in ruins and one well preserved, as well as informed me of a time when both communities worshipped alongside with the sounds of the aazan and the chant of the pandit sounding in sequence, if not in unison. I could only wonder if religion can ever be a salvation, for the majority or the minority, if humanity is lost.

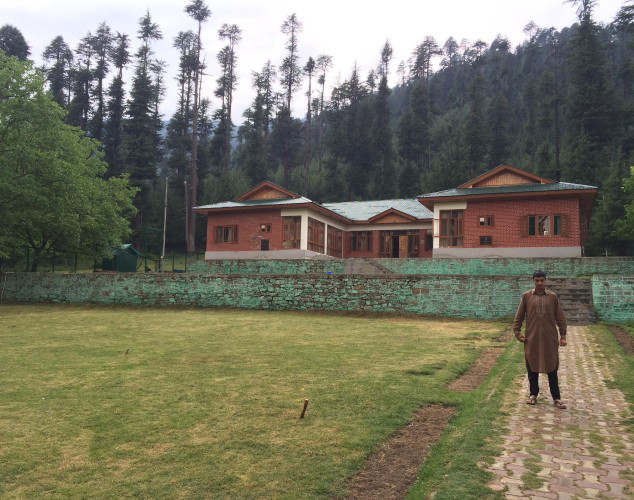

Schools

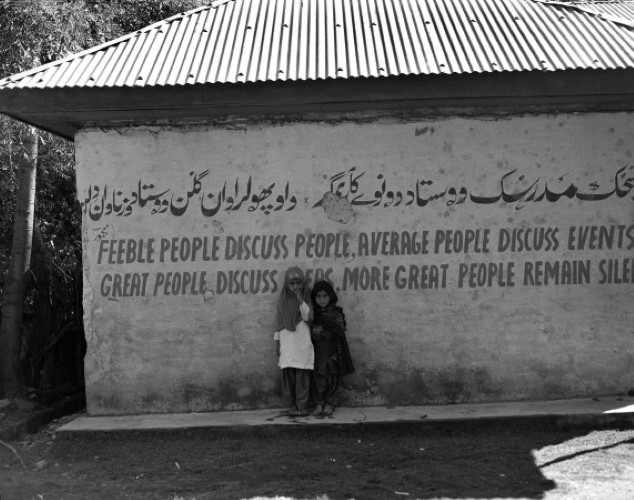

Children were off to school early; In Chandigam they went to the village Madarsa till 8 am, then at the regular day school from 10 am to 4 pm. Chandigam, with a population of 5,000 souls, has 7 primary and 4 middle schools; 2 of which are private; and one Army Goodwill School till the 12th. It seems the Army school has the best reputation, studies happen there.

I stop at a high school on my journey, when the morning assembly was underway under the watchful eye of well dressed teachers and the principal; with sweet girls in abaya squatting on their haunches, separated from the boys. A young boy; terribly gangly, nervous and very teenage was reciting 'We Shall Overcome’ in Kashmiri-accented English. The skepticism that accompanies experience makes one usually ignore the positive heart of this song, but at this unexpectedly vulnerable moment this brought back faded memories of my childhood in a Delhi Jesuit school; and brought me face-to-face with hope in a strife torn land where the ability to dream for a brighter future must surely have died a thousand deaths. ‘We shall live in peace one day', he sang on as his admiring schoolmates looked on; I was the only one facing an epiphany. None of these sweet children could possibly comprehend what the young man is reciting in an alien language, they do not know what they need to overcome, if they can. I am momentarily overwhelmed by the burden of my knowledge of living, of this fierce conflict, of looking at the faces of these children who don’t know what challenges life in this land will bring to them. ‘Living in peace’ is a cry that goes straight to my heart, and my eyes go moist; deeply feeling the futility and suffering inherent in human life, and the coming sadness in the lives of these youth.“People forget that their lives will end soon. For those who remember, quarrels come to an end” the Dhammapada says. The moment passes.

A permanent teacher earns 25,000 rupees a month, and each of those I saw at the schools looked in great physical shape, with visible hints of prosperity by way of a paunch quite unlike the vast number of villagers whose children are enrolled at the schools. Some of these teachers don't believe there is ग़ुरबत, at least not hunger. Everyone gets ration from the public distribution system, they say, ‘below the poverty line’ (BPL) gets 35 kg of rice at ₹3 a kg, 3 kg of wheat atta at ₹3 a kg; and 2 kg of sugar at ₹15 a kg. However, wily shopkeepers siphon off and sell this rice at ₹20 a kg, and people buy it as the open market white rice is priced at ₹30 a kg. The ingenuity of the corrupt Indian reign supreme, and collusion of the bureaucracy. Just for this ability, India, Pakistan and Bangladesh are clearly recognizable as one nationality.

Himal Warnau, Lolab Valley, Kashmir

We stop to have lunch at a teacher’s home in a Gujjar village, his wife a childhood friend of Bashir's wife. It was raining, and with hopes of photography washed out, we sat around sipping hot tea, and chatted. Government teachers are scarce, he says: there are only 2 in his primary school, where grades 1 to 5 are taught, with 10 children in each class. They usually combine the children in grades 1-3 in one room, and grades 4-5 in another, so as to be able to manage the numbers. He asks why does the government not appoint more teachers that are required to cover the subjects and the numbers? He feels the private school lobby does not allow a full complement of teachers; but I know the reality is that the government budget simply cannot afford to appoint teachers at the UGC mandated high wages for government teachers: the wages have been pushed up by the teacher unions themselves, they really don’t care about the children as they have their high-paying and ‘permanent’ secure government jobs with life-long pensions. Hence, the state education budget can handle only so many permanent teachers on the employment of the government; whether it serves the need of the children is unimportant. The system is stuck in an impasse, with less than half (often, one third) the complement of the required teachers in each school, and the teacher's unions unwilling to reduce the relatively high wages of the existing lot to enable hiring of more. A previous government, of late Mufti Mohammad Sayeed, had started a temporary, associate teacher scheme in the year 2000 perhaps to get around this very impasse; called the Rahbar-e-Taleem, which has been stopped for some years now for reasons unknown. No wonder the most sought after job is that of a government school teacher – she is respected, well paid, secure, and doesn’t have to work unless she wants to.

I learn that the families of these 50 students are poor – either laborers, marginal farmers, or nomads; and they cannot support their children’s education. Parents don't, for example, help children with homework, as they are uneducated themselves; those children who have older brothers and sisters are better off. In this area, only 1% of the students go beyond grade 8; and none of the girls do. In the last decade, though, more schools have been setup than ever before and more children than ever are going to these schools. The quality of education is obviously another matter.

Sivar Maidanpura, Lolab Valley, Kashmir

We continue, over the coming days, to visit schools in Lalpora, Warnau village, Himal and Aphan mohalla. Young men hang out in the village square and are happy to pose for photographs in the faint hope that I will bring their plight to the attention of someone who will do something for them, all are 12th grade graduates without jobs or indeed hopes of one.

Sivar Maidanpura, Lolab Valley, Kashmir

We carry on to Sivar, Khurama village, and then to the Maidanpura school, where we meet two sweet young girls who stand out from their schoolmates by their shy energy and a bold dream – they both want to be doctors.

Kakar Devar, Lolab Valley, Kashmir

We end up walking into the primary school in Kakar mohalla in Devar. The school has 6 grades (1 to 6), with 66 children mostly from the Gujjar nomadic community, 2 teachers and 3 classrooms. They should have 5 teachers, and 6 classrooms; and the teachers should teach. Parents take their children away when they go into the hills for grazing their cattle; they need the extra hands and in any case where will they stay in the village without the parents, specially the young girls? The government has a scheme for mobile schools where teachers are expected to follow the migrating nomads, followed in the breach. The second teacher, a Madam, came in as I was leaving - at 10:40 am, driven by her husband in a Micra. She was a healthy woman in her mid thirties, and overweight – a rare sight in Lolab. I saw the uncertainty on her face as she stepped out of the car, maybe I was an inspector sent by the authorities to report on the school? Her fear faded as I continued on my way out.

So many schools, so many partly literate; and no jobs either for these partly literate, or indeed for the more educated. If this is not a recipe for social disaster, then what is. This, I am quite sure, is the vacuum into which religion steps in – at least, there is certainty at the madarsa, someone qualified teaches there, the Book and the knowledge is proven across millennia, and once gained the knowledge gives safety in the hereafter too.

Schools, as I can vouch, are everywhere, though (as I learnt after visiting a score of them), little of value takes place within even when compared to the abysmal standards in other Indian states. The question then is one of quality, not of numbers. In a 2004-05 ranking of pupil achievements in 20 Indian States, J&K was at the bottom of the barrel – worse than terribly uneducated Uttar Pradesh – only 26% of children 8-11 years in a government school in Kashmir are able to read; only 50% can subtract and only 67% can write.

Farming

We see younger and older farmers (Dandhvol) walking to and from their fields with their ploughs (alboin). And many families have a gav, the cow. There is an organic connect from the distant common past of Persia and India, thousands of years back, when the Gau gave its name to gotra, a closed endogamous group. More than anything else, the cow connects Persia to India; and Kashmir is in many ways right in the middle. It could be a unifying culture, a transition from Persian to Indian.

It was the season for rice planting, and the fields around the villages of Lalpora, Charaligundh, Radnagh were filled with very busy men and women planting rice seedlings. The season commences end May and ends 20 June all over Kashmir, in Lolab the planting will mostly be done before the month of Ramzan starts on 7 June. For over a month, everyone from the village is deeply involved with the rice sowing; the city-employed return home for a couple of weeks to give a hand. Men plough the fields in knee deep water, and direct the recalcitrant bulls; women plants seedlings in unison often on song, and as one drives by one sees groups of men and women sitting together in groups having a picnic with noon chai and roti. It's a full day's work, and they all visibly exude camaraderie; singing and breaking into laughter as they rib each other. Families work together, first on the land of one and then in sequence for the others. It was all quite idyllic, with majestic mountains ringing the fields in the valley, bulls going though the water filled fields, their alboin calling out to direct them, Poplar trees, clear blue skies, clean sharp cool air, a bright sun, and sounds of happy people and thier laughter ringing through. Who would have thought this is a deeply troubled land.

Road Dardpora, Lolab Valley, Kashmir

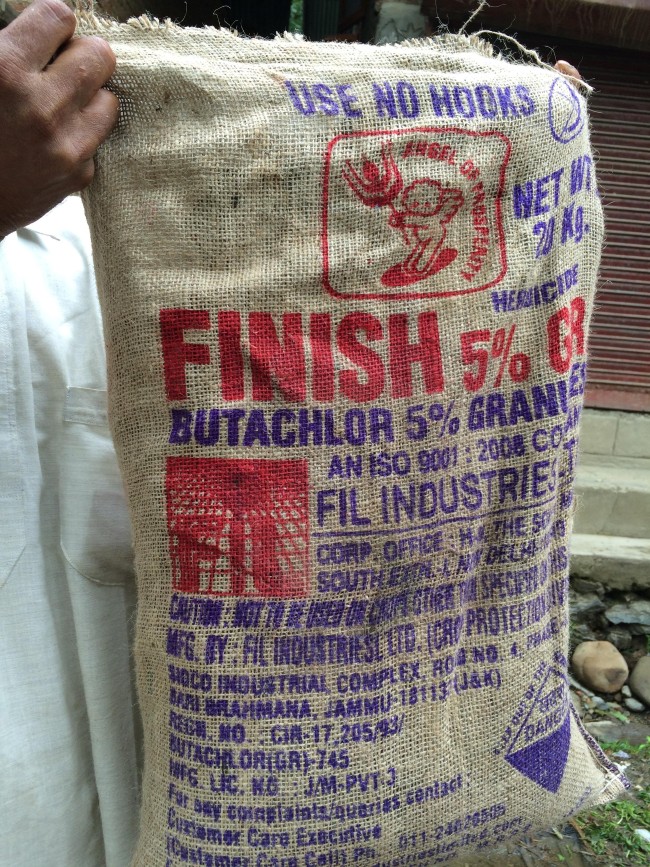

Rice is the major crop in Lolab, for which ploughing commences mid-March. Peasants yet use whatever gobar khad, cow dung manure, they have at home though extensive use of commercial chemical NPK is mostly the norm. I saw everyone using the herbicide ‘Butaveer’ from Chambal Fertilisers; appropriately called Finish. It makes life easier, peasants tell me, once sprinkled in the land the weeds disappear. Boom. Before this, everyone had to spend endless days de-weeding by hand twice in the season. Now just one application of this herbicide, this poison, is enough. Many sprinkle it multiple times, after all it is ‘dawai’ or medicine.

A state horticulture department employee says everyone sprays pesticides vigorously on all fruit crops, across Kashmir. Apple has 4, even 5 sprays. Badam, cherry, akhroot, khubani, apricot. All. Why, I ask? He shrugs, that is the modern way. Fruit commerce has increased hugely in past 20 years, and everyone uses pesticides to meet the demand and the increasing incidence of pest infestations. Where will this end, I wonder. Most probably when there is no way to return.

The Kashmiri public sense of hygiene is as terrible, and the streets and public toilets are as filthy and strewn with plastic and packaging detritus as elsewhere in India. The weather and the stunning natural surroundings, however, make it this absence of civic sense so much more palatable.

Livelihoods

There is little employment in Lolab; the most coveted category being that of a मुलाज़िम, (mulazim, or a government employee) as a teacher or a bureaucrat; where high wages, lifetime employment and little work is the norm. These plum jobs are reserved for the political elite and their hangers on, and remain within this small, charmed circle. There is no organised private sector, and no tourism - sensitive, or senseless. Private schools abound, with teachers on salaries as low as 30% of the government teacher wages which is more a function of thousands of desperate, educated unemployed youth than only a real statement of their worth. Some of those who don’t find jobs become shopkeepers, selling low value goods at basic shops of all kinds, eking out a living and passing time. The only other category of work for the poor majority is मज़दूरी (mazdoori): labor for hire in farming or as daily wage labourers on construction projects et al. As we visited distant villages, this was clearly the predominant form of livelihood – a hopeless existence in desultory employment of hard labor, poverty and illiteracy.

A grizzled, older villager says the young boys today are useless for farming. School educated, they don't really know zamindari as they were away in school during the time they should have worked in the fields; and neither do they have any interest in the combination of subsistence farming and mazdoori. They can be found sitting around the village square waiting for a future. It is not an unusual sight for any of us who travel to villages and small towns in most states of India, but the reality of experiencing it all days, in every village was numbing.

Needless to say, corruption is endemic. All government functionaries are on the take - from ministers and their hangers-on, to the bureaucrat and the lowest panchayat functionary. I was too emotionally exhausted to investigate if this corruption is deeper and worse than in the rest of India, but it really wasn’t worth finding out. The situation on this front is grim, and it was futile to explain to the locals here that this is the situation all over the nation. “हिंदुस्तान ने हमको कुछ नहीं दिया”, says a particularly voluble man in Dardpora, “the politicians eat all that Modi gives; all the 80,000 crore rupees”. “Where is it?” he asks me rhetorically, pointing to the scraggly, dirt road in front of his house.

We meet a Parmi family, supposedly from Kagan in Pakistan Punjab, their nomadic origins lost in time - a time they were Rajput, but that is too far back in geography and time to verify. The old patriarch we meet is said to be 160 years old, his memory non-existent. We spent time with his daughter-in-law, and her children with beautiful, violet eyes.

Dard means Pahari, and Dardpora has both Pahari (also called Parmi) and Gujjar people. We drive past a house blown up 2 months back in an army operation on militants holed up inside; its eerie, a single charred shell of a home in the midst of green, verdant mountains. The very next night, on television at the Chandigam rest house, I followed an unfolding ‘breaking’ story of militants in nearby Kupwara surrounded by the army and the house was blasted to get at these militants. This story is not an isolated one, the Army has to do what it takes to dissuade the locals from harboring militants on the run. If the cost is a house or two, so be it. Everyone is used to conflict and destruction, it is part of the environment.

Shalpora Lalpora, Lolab Valley, Kashmir

We meet another young teacher brother and sister pair, Shamim and Asiya, beneficiaries in 2008 of the Rahbar-e-taleem (RT) scheme that enabled unemployed, educated youth become trainee teachers at low wages. Their ancestral house was burnt down (a beautiful deodar wooden home, with that unique scent of the mountains; we visited its remains) in the usual militant and army firefight in 1998. Their father, a Parmi, is till today a mulazim in the Government, the only villager who was one. After the house burnt down, he fled to the nearby town of Kupwara and made a life there, taking his two children with him. They studied in Kupwara schools, away from the traditional and conservative village, and this clearly changed the trajectory of their life. They recognise that their Parmi community is not yet committed to education, and that their father is special by his focus on education. Neither of these youth, or their spouses, are liberal in their worldview and are in fact torch bearers of tradition; but are yet ‘modern’ in some confused ways. I didn’t see these women wearing a burka, for example, and their role as a bread earner gave them a visible confidence. But the norms of religion and tradition clearly define their traditional position vis-a-vis their spouse. This seems to be the norm in Lolab – where there is educated youth, it is yet terribly conservative. The story of small town India.

The State

People tell me that the government doesn’t deliver, surprisingly they blame Modi even for the drop in the price of akhrot giri as the government is said to have allowed imports of walnuts. Everything is a dark conspiracy brewed in Delhi against the Kashmiri. No one seemed particularly happy with the PDP, or with politicians in general. Ministers and the Sarpanch provide patronage to people who are their diehard supporters or part of their extended family; for example, under a state sponsored scheme to build homes. Or if you gave 16,000 rupees to the Sarpanch you could get the money. Simple.

The natural and human-created calamity of the 2014 floods in Srinagar valley diverted the limited capability of the state to fighting it; and this bleak view of the capability of a corrupt and inefficient State has loud echoes in Lolab. The PDP didn’t look like they were going to achieve anything out of the ordinary, and there is no trust in Delhi. People question “Where is my 15 lakhs rupee? Where is the 80,000 crores he gives to Kashmir?” While everyone rushed to banks to open accounts under the recent Jan Dhan scheme, where the rumor said Modi was going to deposit money in every account, one skeptical man told me he didn’t open one “ …I'm not going” he told the rest “…but let me know when you get money in your account, I'll open my account then”. It would be terribly funny if it did not reflect the desperation of the people to believe a silly rumor like this one, as well as the lies the system constructs in the absence of the real work of public service by public servants.

I visited a number of villages where well constructed panchayat buildings lay deserted; not yet in disrepair, as they were constructed recently by the previous Abdullah regime as I saw in the foundation stone ( “… inaugurated by Janab Omar Abdullah …”); but locked since inauguration and never used. These structures add to the belief that politicians construct infrastructure to feed the corruption of their followers, little else.

Kakarpati Devar, Lolab Valley, Kashmir

Wherever I stopped, I received an outpouring of love and affection from strangers, and an equal outpouring of their tales of their woes of poverty and hopelessness. Bashir had used the Indian talent for twisting the truth by telling all and sundry that I was investigating ग़ुरबत in Lolab (which was true) but he also led them to believe someone in Delhi and Srinagar would read my ‘report’. He was careful not to say I was with the government, or that anything would come out of it, but people did not need that commitment. In remote Gujjar villages, some people were glad just to have someone to unload to. This left me with the responsibility to share the story of their poverty, their frustrations; did they think that maybe I would - just maybe - take the story of their problems to someone who cares? Family after family, I heard stories of suffering, poverty, illiteracy, unemployment. It would all have been too much for me to handle had there not been children around who didn’t know what they didn’t have and were happy just being children. Knowledge that comes with age is overrated, certainly doesn’t equal happiness.

Road to Dardpora, Lolab Valley, Kashmir

I didn’t see too many state road transport buses on the road, and the few I saw were clearly in a pretty bad shape. Some of this was a function of poorly maintained roads, but one story of callousness is simply breathtaking - Bashir once travelled to Delhi on a government bus, he says it had 15 punctures on the way. Discounting for hyperbole, it doesn’t take away from his conviction that drivers and officers of the agency conspire to sell new bus tires in the black market. Maybe the same goes for engine parts, and I envisioned a bus hurtling down potholed dirt roads on the mountains without an engine inside ….

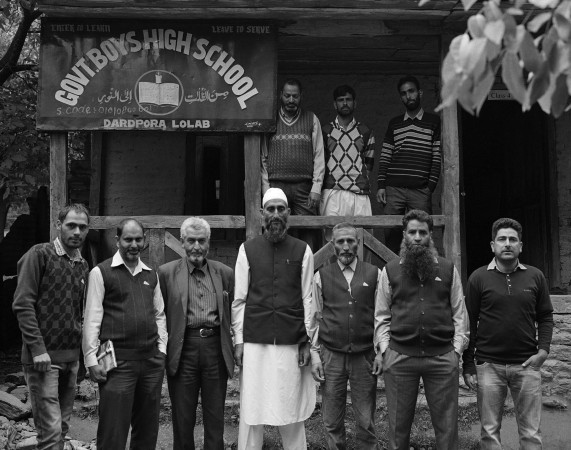

Families

I had voluntary guides galore for walking around the village mohallas, perhaps it was due to seeing a tourist; a rare sighting in these times, certainly no tourist in recent memory had walked inside the villages and visited the schools talking to people. Unemployed young men with little to do abound in the villages, though that cynical view does not do justice to the inherent desire for mehman nawazi of the average Lolab family.What wonderful hospitality from complete strangers wherever I went, insistent offers for tea, and equally insistent requests for staying at their homes overnight. Poor and little income, but they will serve you all they have. I am told “Pahari dil ke sacche, aur akal ke khote”. I was invited to numerous homes, carefully away from the women folk, where we were seated on quickly spread out Kashmiri carpets, and the men served us tea, biscuits and dry fruits as we discussed the poverty and absence of livelihoods in Lolab.

We had a lunch at Bashir’s distant cousins home, where he had called ahead to warn them that a vegetarian guest was coming. My poor hosts were apologetic and quite depressed that their guest only ate vegetables and they couldn't serve him real food! It was punishing for me even then, as poor man didn’t know what to do in place of meat for an honored guest – I was served potatoes in a gravy of oil, and rice. Yes, a gravy of only oil.

Kashira Bala, Lolab Valley, Kashmir

The village of Kashira was an eye opener. Predominantly Gujjar, it also has villagers from other castes - chauhan, bara, badana, chechi, tench, bania, melu. Every family seemed dirt poor, mostly illiterate, and with 6 to 10 sweet children. The Gujjar families are on paper provided reservation in state employment, as they are Scheduled Tribes; the irony is they need to be 12th Grade pass to be eligible for these jobs. Not happening anytime soon.

Kashira Bala, Lolab Valley, Kashmir

I meet an old woman whose eyes teared-up when she talked about her loving daughter who died, and a nephew who also died. This sense of multiple loss makes her love her grand daughter that much more, the innocent girl giving strength to the grandmother. We spend time with another matriarch with 4 sons and 2 daughters; dirt poor; with 2 kanals of rocky land with each son who are mazdoors. No irrigation water reaches up here, there is no drinking water either; and the nearby rain-fed stream dries up in July. Her cup of sadness runneth over as she says, pointing to her cell phone, “tower bhi nahin!”. Even the Kashmiri telecom gods conspire against the poor.

Kashira Bala, Lolab Valley, Kashmir

Little Nagina has 5 sisters and 4 brothers, her mother looks like she would be in her late Thirties. Nagina doesn't go to school, only goes for basic Koran reading, Qaeda. We meet many families, all quite similar, who have lived village lives for generations at the periphery of Islam, following their tribal Gujjar traditions. Today, no community or village in Lolab is far from the call of conservative Islam, and the assimilation of these once-heretic Gujjars is an ongoing process; certainly speeding up due to the increasing number of Masjids and Madarsah's across Kashmir that proselytize the right religion and teach the right traditions.

Kashira Bala, Lolab Valley, Kashmir

In all these homes in Kashira - 100 to 150 families, 10-12 people each - the maize crop has failed this season, pests ate the maize seeds sown in the fields. They planted again, but is too late for a crop. Besides the key issue of food insecurity in the here and now, they will have big problems next year for seeds as they typically save seeds from this years harvest for the next years crop – no one has money to buy seeds from the market. This is subsistence farming, my city friends, where the family lives off small parcels of land dependent solely on rains for a yield. If the rain fails, the crop fails, and they are on the verge of starvation. Thanks to ration cards, though, they don't die of hunger.

Kashira Bala, Lolab Valley, Kashmir

It is time to depart, and we walk around Chandigam early morning before we set off to Bashir’s home for lunch, halfway to Srinagar and the airplane home. I experienced the reality of everyday life in Kashmir; where daily worries are about livelihood, education, health and corruption like everywhere else in India. It is never really that only, as religious and political leadership rule and divide for power and wealth. Poverty of the human mind is all pervasive, Lolab cannot be an exception.