This visit to Kolkata was to document the madness that is the Puja season; I thought it would be a cool adventure, Bengali friends looked at me with pity, some with silent amazement. I understood their gaze when I walked around Ballygunge on my first evening: Kolkata streets during Puja are crowded in a way that cannot be described, Delhi’s Chandni Chowk is a walk in the park. Puja pandals are in the thousands across the city; newly prosperous businessmen, politicians, shopkeepers in local communities building elaborate, temporary structures along and on the roads and alleys of a city already bursting at the seams. The democratization of life and capital in Bengal has brought to the fore a new benefactor, with money and desire for social acceptance but without the sensibilities that accompany generations of privilege. Traditional Pujas continue to be held by established families, in enormous, stately, rambling homes that have gone to seed but remain breathtakingly atmospheric for the photographer and those with memories.

I visited numerous pandals, with gradually diminishing interest. These were all new, homogenous idols of Durga and other figures, put-up to be taken down, and without the deep imprint of the belief of people that is so unique in Indian places of worship. The puja at the older, once-wealthy family homes however had a depth that older architecture provides. I spent time at Rani Roshomani bari, on Ashtami, on the side housing the many descendants of the second daughter. The hospitality of the Bengali came home to me, again, when I was plied with lucchi poori lunch by my hosts, and I was invited to witness the Kumari Puja, the worship of the virgin Durga. The sweet 6 year old, ever so shy, quite enjoyed the attention of the gathered family.

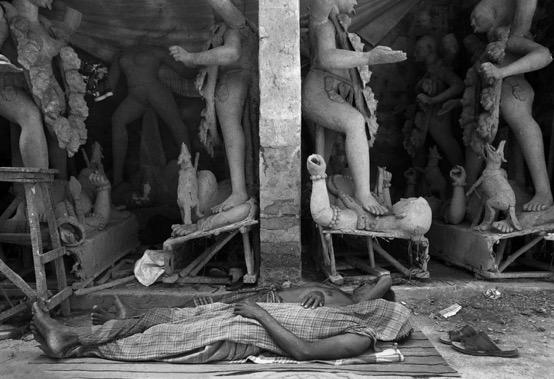

Kumhartuli, the locality where the idols for Durga and Saraswati puja are hand crafted by potters using artisanal methods, was fascinating. Generally, we are witness to the destruction of the livelihood and skills of our impoverished artisans, and it was heartening to see the retention of traditional artisanal skills as well as the application of natural materials – straw, bamboo, Ganges mud – that go into the construction of the idols. The narrow lanes of Kumhartuli bustled with groups of sweating laborers carrying idols of all shapes and sizes and calling out to clear the way ahead as they struggled with navigating the lanes and the weight of their loads. I was electrified by the intense atmosphere of so many contradictory factors: the amazing artisanal talent that makes beauty from mud and straw, terribly emaciated migrants laboring to make a meager living, or in deep sleep after a grinding days work. I too was sweating profusely in the humid heat, hemmed in by the workshops on either side of filthy, crowded narrow, narrow lanes. It couldn’t have been a more intense experience.

I rediscovered the gentleness of the Bengali not aroused by religious strife. Street directions were given freely, at leisure, and with concern at your getting to where you want to go. Women and young girls were walking around with confidence at all times, a surprise to a street-hardened visitor from Gurgaon. The educated Bengali in Kokata seem ever so much more genteel than the Bengali outside Bengal.

An interesting attribute of Kolkata garbage is its organic nature; there is filth, and it’s very much on the streets, but it is less consumer and plastic than Delhi. Tea is yet served in a mud kullar, there is extensive use of bamboo for all kinds of purposes from pandal construction to road dividers, idols are made from straw, flowers are offered to the gods in smaller pattals (dried leaf containers), and food served in leaf pattals too. Benefits of backwardness, or remnants of an organic past?

I heard from just about everyone that the popularity of the current ruler Mamta Bannerji is on the downswing – whether this is a secular trend due to her much discussed capriciousness, or it is the general disillusionment that sets in when the political messiah is found to be more political than messiah, only time will tell. The BJP was on the ascendant, going by the odd street conversation and the many political hoardings. The high percentage of Muslims in Kolkata and Bengal generally meant this would be par for the course.

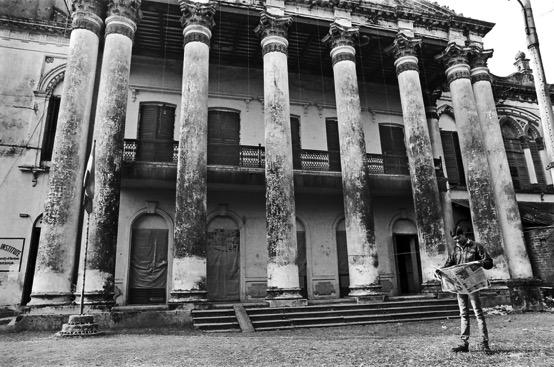

Kolkata has been hit hard by the changing fate of Bengal. In a brief historical space of two hundred years, it was raised to the heavens and dashed to the ground by the British colonialists, and subsequently trampled on by the brown masters each time it struggled to get up. Kolkata was also the foundation of the colonial British empire that brought untold wealth to the privileged locals who serviced the Empire; and the home of an indigenous Hindu cultural renaissance unlike any India had seen, from Roy to Aurobindo, Ramakrishna, Vivekananda, and Tagore.

The British treated Kolkata cruelly by transitioning the capital of colonial India to New Delhi in 1911; by making and unraveling a partition into East and West; and induced two famines by their callousness and apathy. The city faced the trauma of Partition in 1947 whose unfortunate story remains overwhelmed by the much worse violence and human depredations in the Punjab. The multiple waves of Hindu refugees to Kolkata since Partition, the massive impact on Kolkata’s civic services due to the further influx of refugees before and after the creation of Bangladesh in 1971 and the continuing flight of the landless and hopeless from Bangladesh, Bengal, Bihar and Orissa has made this once briefly great megapolis an urban nightmare.

Civilizational decay is apparent to any observer, historically well informed or otherwise, especially to an outsider who has the luxury of being there for a brief while, and is riveting for the documentary photographer. I resolved to return to once Regal and British Calcutta, its heritage overwhelmed today by banyan trees, the ravages of time and the uncertain promise of Mamta.

My visit was cut abruptly short after what seemed like a satisfying session of Bihari puchka, cheela, matar chaat and sweets from Gangaur on Park Street. Food poisoning happened, and I was back in Gurgaon the next morning.

Rabab did not let me give up, and cajoled me to continue my interrupted journey to Gurudev’s Shantiniketan in Birbhum district in January 2015. On reaching there, I looked without success for the saintly figure of a teacher under the Barh tree; I found the Santhal instead. The nature of their simple lives has aroused an attraction from deep within that is hard to describe – the Santhal village and people are so much more innocent and so different from my Doab village, yet strangely familiar defined as they are by agriculture. In this attraction, one key component is a desire to reduce life to the basic, simple, the ascetic, close to nature, without the complications of urban life. My reverie was broken by the sight of drunken Santhal men staggering around doing little, while the women work themselves to the bone. Familiar.

It was Basant Panchmi and Saraswati Puja, and the complete disregard for others preferences in music and volume evident in UP was here too - there are many surprisingly unfortunate things common across our country than there should be really, seeing how different we are. Well, the other community waits its turn to crank up the volume.

The Santhal village of Muchipara near a reserve forest patch was illustrative of the genre. The village was clean as a whistle, equally a function of the absence of plastic consumerism and the presence of pigs. There were many men high on local booze, and I am not sure it was the festival season or just how life is. There are no jobs, but is that the excuse for a life lived in a fog of addiction. The women continue to work the house and the land.

Life revolved around the rhythm of agriculture, and this was rice-planting time. Rice from the previous harvest was drying everywhere, including on the roads. And farmers were sowing green rice seedlings from their nursery to the field. The women mix rice straw (khor), with ash (chaie), and mud and paint with this mixture on the walls of their huts. All homes have a rice storage structure within, a Dhaner Moraiye, which can safely retain rice for a couple of years – no cement, no chemicals, only a brick base to raise it off the ground, and a layer of bamboo. There was no pollution, silence of the sweetest kind, and no plastic to be seen. Agriculture was clearly subsistence, or with a minimal surplus. Each village had a water body, a pukuur, bringing to mind the village of Satyajit Ray’s movies.

There is no beauty in poverty, and it’s equally breathtaking to view the self-centeredness of people, like me, who live with so much in a country as poor and unequal as ours. I resolved once again to help build bridges joining the reality of a better future resident on islands of ostentatious wealth, and the hopelessness on a vast ocean of grinding poverty. These photographs are a part of this self-awareness.

When I hit Durgapur, the steel town on route to Bishnupur and the terracotta temples, all doubt on whether it is right for us to want to 'keep' the Santhals in organic simplicity and poverty fled. If this is the future of new India, send me to a Santhal village anytime, with all its issues. Polluted river, half constructed roads, filth, unbelievably crowded hovels, uncontrolled vehicular and factory pollution, and no urban planning of any kind. It was quite hopeless.

I travelled to places with atmospheric names - Dadhia Bargiatala, Nanoor, Itanda, Ilanbazar, Kalikapur, Surul, Supur, Saupukar Danga, Bidyadharpur, Panchmora, Phooldanga. On reaching Hetampur, I was adopted on the main road itself for the next 4 hours by enthusiastic and welcoming local resident Reza-ul-Karim – he showed me all the Hindu temples and local Rajbari, without hesitation in entering any temple. Bemused by a Delhi man with a camera this far from anywhere, photographing without objective, he eagerly took my mobile number as he bade me farewell.

My number sits silently on the phone of a kind man I will not meet again; helpful, generous, caring man who held my hand and helped me cross - fleetingly - the identities of class, religion, region, language and caste that hold our unequal nation in their fierce octopus grip.