Sunrise on the Brahmaputra, Kamalabari Ghat

It is forever a marvel how air travel enables one enter a parallel world, at such short notice; when there, I never stop thinking how people live their lives at the same time I am absorbed in mine. Travel photography is simultaneously meditative, outward facing, and regenerating: in these distant places, I sense a heightened feel of the other; think outside my self-inhabited world; and fleetingly acknowledge the irrelevance, fragility and transience of life before the security of home brings me back to my temporary permanence.

Flying to Kolkata from Delhi and onto Jorhat, a taxi ride to the banks of the mighty ocean-like Brahmaputra, on an overloaded ferry packed every inch with produce, people, cars, and motorcycles; reaching the island of Majuli. There, within 10 hours, I was thrown into in a world living in a different time; in a leisurely, rural rhythm; in a culture familiar to a UP-wala and yet so different from the one I left behind in Gurgaon.

Majuli is a stunningly beautiful river island in Assam, one of the largest in the world, 200 kilometers north of Guwahati, where a gentle people live an agricultural life amidst wide swathes of rice fields. Villages are built organically with bamboo homes on stilts, narrow tree-lined roads, scores of water bodies and rivers, vibrant animal and bird life amidst vast groves of bamboo and majestic trees. It has a stillness and simplicity that is peculiar to places that live in proximity with nature, a cumulative effect of the absence (or at least the significantly reduced presence) of speed, plastic, cement, steel, glass, people, automobiles, and mobiles.

Majuli’s peace and quiet is deceptive. This 450 square kilometer island has shrunk to half its size in the past couple of decades with its sandy banks eaten away by the powerful waters of the Brahmaputra that swirl around it. No one quite knows how to combat this force of nature, and we are told that Majuli will cease to exist in a couple of decades if not sooner. Will it? More than poignant, it’s surreal - people live in a land where their homes, livelihoods, their way of life won’t exist soon. The powerful forces of destruction and creation work alongside, in cosmological Hindu time - people go about their life, knowledgeable about impending doom without panic. We all live with the certainty of death, but the world we inhabit stay on. Here, that too crumbles.

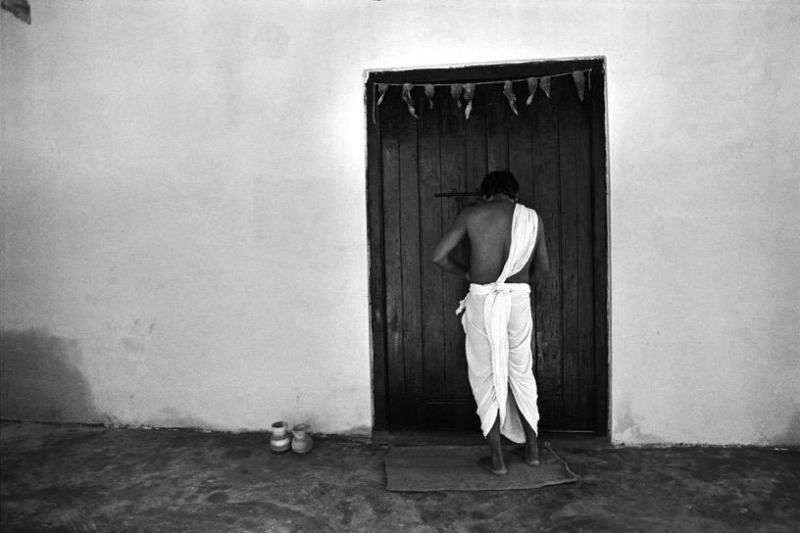

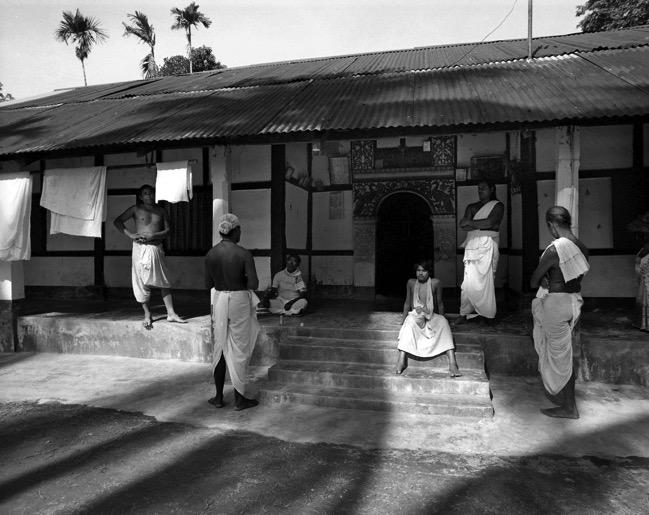

Mahapurush Sankaradeva. To an itinerant documentary photographer seeking sacred spaces, what makes Majuli especially fascinating are the hundreds of Vaishnava monks in the 22 Sattras (monasteries) where they live in the Guru-Shishya parampara: where both student and teacher stay together joined by their desire for spiritual and religious learning. Many of the original 65 Sattra’s have been washed away or have relocated to the mainland, but Majuli yet retains the most Sattras in any one part of Assam. I never could have imagined that this tradition remains alive, but here it was – thousands of years of monastic tradition preserved organically in time.

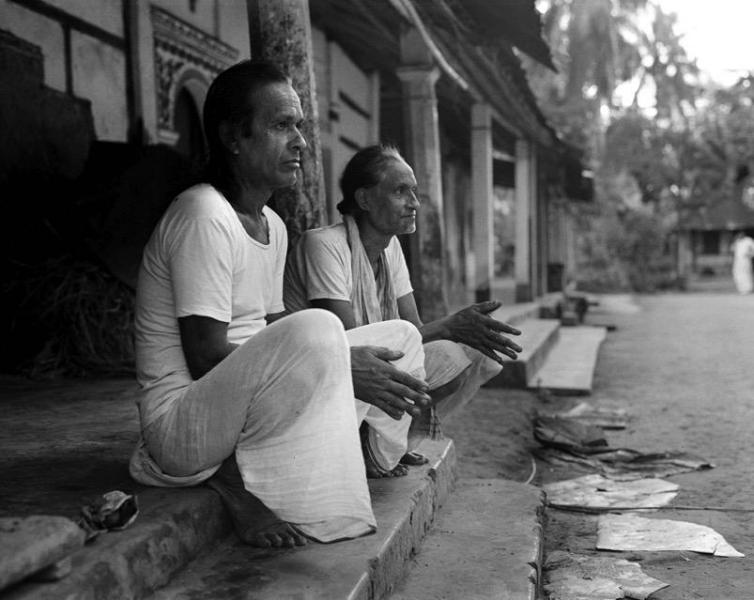

These Vaishnava abodes remind me of Buddhist viharas, with monks of all ages living a disciplined life that revolves around scriptures, prayer, dance, music, rituals, festivals, and food. Even the musical instruments – the big drum, the bells, and the cymbals – sound an echo from the Vihara. Life here is yet predicated around agriculture, and the rural rhythm of life defines the activities at the Sattra - the fertile land and the bountiful river enable them be self-sufficient in food, there is no hunger. The Sattra takes us to a society and community where the village and the monastery lived in symbiotic co-existence, one giving physical support and the boy child; and the latter a spiritual framework to lay people trying to make sense of life and death. This symbiosis remains true today; the continuity is remarkable as society lives in multiple centuries at the same moment. I panic about the disappearance of the past from these Sattra’s, their organic heritage in danger of disintegrating and being replaced by a uniform, industrial, artificial, engineered world. They can’t hide.

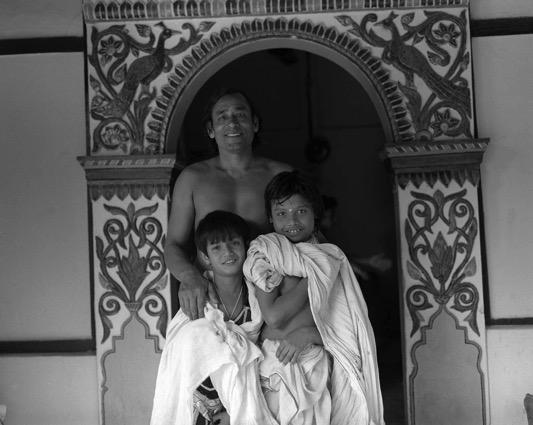

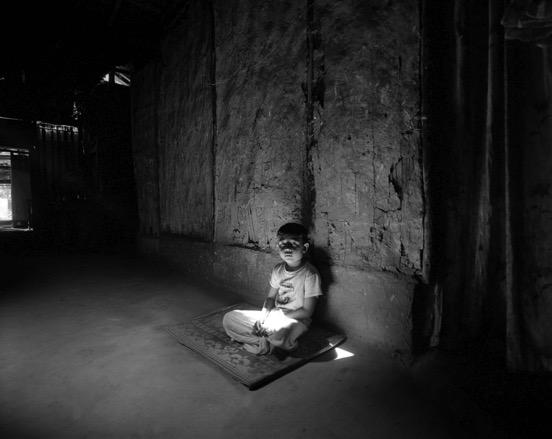

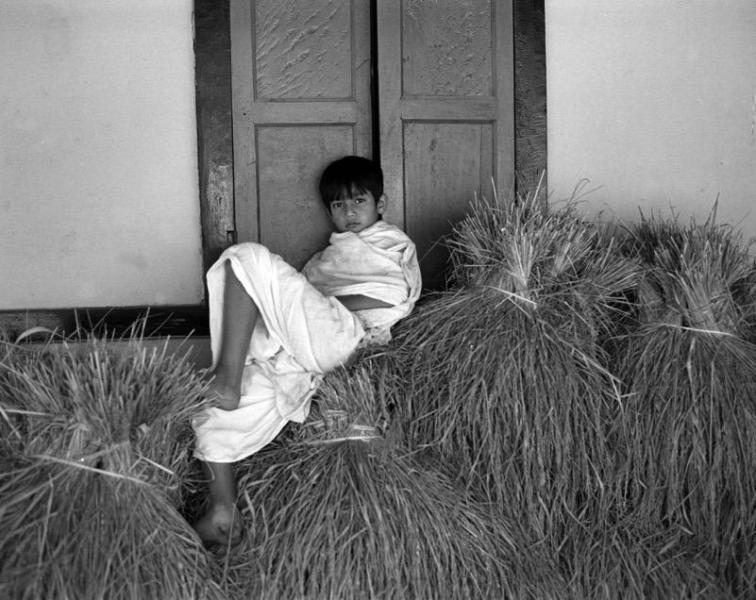

Young bhokots at Dakhinpath SattraYoung bhokots at Dakhinpath Sattra

Young bhokots at Dakhinpath SattraYoung bhokots at Dakhinpath SattraYoung bhokots at Dakhinpath Sattra

Mahapurush Sankaradeva, the founder of Assamese Vaishnavism, sought answers to the questions of this brief existence in the many scriptures of the Hindu faiths, answers that resonate across religions for those willing to hear, questions the atheist can also spy beyond the words. Born in 1449, Sankaradeva live for 119 years and established the Sattra tradition of Assam. He was an effective and creative communicator, the original multi-media man with his unique repertoire of original poems, prose, songs, paintings, dance, instruments and music. He was a uniquely talented man, single handedly establishing the foundation of contemporary Assamese religion, art and culture. He a scholar in Sanskrit, translated the scriptures into the language of the people; wrote bhakti poems that he set to music based on classical raga’s (many of which survive till today); wrote theater in Assamese that took the Raas Leela and other forms of Krishna worship to the people through creative dance, music and lyrics. After 10 days in Majuli, I realised that Assam breathes music, dance, and Krishna.

Similar to what the Guru Granth Sahib did for the Sikhs, Sankaradeva gave the Assamese the Bhagawata to replace all idols. Not quite possible in Assam as elsewhere in India, but this Mahapurush tried.

Eka deva eka seva

Eka bine nahi kewa.

One God, one devotion,

There is None but One.

‘Simply singing of and listening to tales of Vishnu or Krishna, and taking refuge in Him without any desire or motive, were enough. “God is accessible neither through penance and renunciation, nor through gifts. He is not accessible through yoga or knowledge; He is tied down to bhakti alone”.’

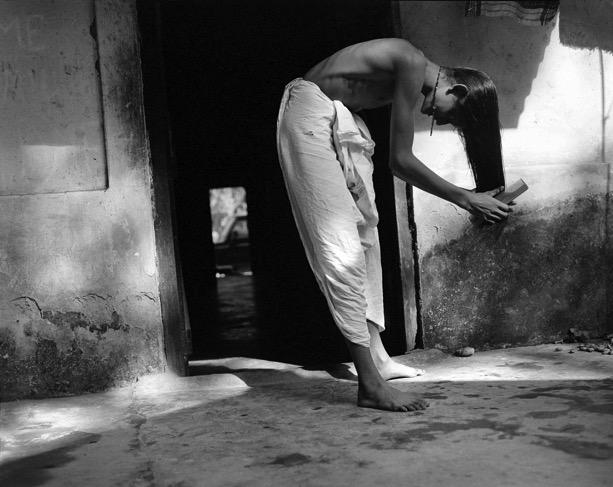

The Sangeet Natak Academy accorded Sattriya, the dance established by Sankaradeva, the status of one of India’s eight classical dances in 2000. I spent time with at Uttar Kamalabari Sattra with the diminutive and gentle Bhabhananda Borbayan, a Ph. D. in the comparative study of classical dance with special reference to Sattriya. It was surreal to hear – sitting in remote Majuli - from a monk with a doctorate that he runs a dance school for Sattra in Delhi next to the JNU campus. It was good to see the flexibility the Sattra provides to the monks, enabling them engage freely with the secular world. Sattra musicians and dancers travel worldwide with their Sattriya, and Kamalabari has established its reputation as the source of outstandingly creative Sattriya artistes. Beautiful male bhokots at Uttar Kamalabari exhibit a powerful sensuality that is perhaps a result of their well-developed creative skills, as music and dance is at the center of life at this Sattra.

Scholars abound at the Sattras – the Natun Kamalabari Saatradhikari (head monk) Narayan Chandra Deb Goswami wrote the authoritative grammar of Brajabuli of Assam, and was awarded a Sahitya Kala recognition for his efforts.

The Sattra. The Sattras across Majuli have musical, atmospheric names: Uttar Kamalabari, Natun Kamalabari, Auniati, Shamaguri, Dakhinpath, Bhugpur, Garumur. Some are wealthier than most, a reflection of the capability of the Sattradhikari or the wealth brought by the large tracts of land attached to the Sattra, or the fame and patronage that a well developed Sattriya dance capability brings in creative Assam. The architecture of a Sattra revolves around the Naam Ghar (prayer hall) established by Sankaradeva whose open architecture brings the outside in, especially critical in Majuli’s mostly hot climate, and is along one length of a central water body. At one end of the Naam Ghar is the monikut where idols of Vishnu or his avatars are placed. Naam Prasang (prayers) from the Bhagawat – the holy Vaishnava book, compiled by Sankaradeva – take place here are held at least three times in the day. Idol worship is secondary; taking the name of Krishna is paramount though clearly form takes precedence over content. The architecture of the Sattra is completed by the simple Boha (homes) of the bhokot’s on the other three sides of the water body.

Daily life at the Sattra is simple and uncomplicated, defined by the rhythm of agriculture and the demands of religious worship and ritual. The boodha bhokot (older monk) is the guru and the head of the household and the young monk is the shishya, in what seemed a warm father and son relationship. Bhokots come to the sattra as infants, and live their lives out at the sattra.

During this Raas Leela, the biological mother and father of many a young bhokot were visiting and staying at the boha, and I could see relaxed, happy and friendly boundaries between them and the sattra. The monks in each boha make their own food, and I had many warm and wonderful meals at a boha of one bhokot or the other, a vegetarian’s delight. I was served as befitting a guest from far away lands, and what food. Rice, with chana dal, moong dal with chole and coconut, aaloo, banana fritters, kumra jhool. With one red chilli. The chutneys were amazing, as was the dessert of a special (Komal Chawal) rice with yogurt and jaggery.

While the Sattra lives in comparatively splendid isolation, integration with modern life grows apace. All the young bhokots now also absorb modern education in schools nearby, in addition to their religious education within the sattra. Then, there are the travels of the bhokots to far away lands for the Sattriya dance. The Raas Leela, bhaona samaroh, bargeet and Gayan-Bayan have taken a cultural and commercial shape outside the religious sphere of the Sattra; with both women and men both playing parts on stage side by side. At the Raas Leela held at the sattra, boys continue to play all the roles. At the same time, a doctorate monk teaches Sattriya in Delhi to anyone willing to pay and learn. The pulls and pressures of commerce from the secular world, and the opportunities, are changing Sattra life and traditions, slowly and surely.

The downsides of everyday exploitation are visible to the objective observer of sattra life. Inequality abounds, under the dominance of high caste men. As elsewhere in India, caste reigns supreme, behind the worship and the rituals. All the happy bhokots are Brahmin Goswami, Kolita, Bora or Borthakur; dalits cannot be accepted into a Sattra, neither can a Mishing tribal, nor a woman. Indian society adds thick layers to the human propensity to dominate and exploit, and caste is impenetrable skin we are doomed to live with. A woman is barred from entering the monikut in many a sattra, including Barpeta on the mainland where the Court had to step in to end the ban on entry of Dalits; women were banned from entering the Naam Ghar in Pat-bausi sattra till 2010. I couldn’t touch the monks of any age at any sattra, lest they be ‘polluted’ forcing them to wash or bathe. And as in any celibate residency, boys and men living together implies sexual exploitation.

My gentle guide and driver, Ajay Payeng, was quite in awe of the sattra and obsequious to the sattradhikari. I learnt that Mishing people like him were at one time not allowed entry into the main gate of the sattra; times have changed and though now they are allowed into the Naam Ghar they cannot enter the monikut where the idols are placed. Despite this, the assimilative power of the dominant religion has ensured that the Mishing worship of nature (the Moon and the Sun) has waned and they have absorbed the ways of Vaishnava Hinduism.

Festival. I had planned my visit to Majuli in November to coincide with the biggest annual festival, the Raas Leela, when the fevered pitch of religious life would add to the chaos of regular life and make documenting exciting. I was not disappointed.

Raas Leela night at Kamalabari SattraRaas Leela night at Kamalabari Sattra

Raas Leela night at Kamalabari SattraRaas Leela night at Kamalabari SattraRaas Leela night at Kamalabari Sattra

Raas Leela night at Kamalabari SattraRaas Leela night at Kamalabari Sattra

Raas Leela night at Kamalabari SattraRaas Leela night at Kamalabari SattraRaas Leela night at Kamalabari Sattra

The music, locale and stories of Krishna were instantly recognizable, sung as they were in classical Indian ragas. These devotional songs, Bargeet, composed by (who else) Sankaradeva are based on over 30 ragas, the more popular ragas being Asawari, Kalyan, Basant, Gauri and Dhaneswari. I watched the evening rehearsals of the public and ticketed event in a large Kamalabari field; the enthusiasm, music and dance were captivating. All Sattras celebrate for a week, when the Raas Leela continues through the night and the spirit of Krishna pervades daily life even deeper. People visit from all over Assam, and it’s one big party. I suspect boys and girls have interesting interactions in the nights.

At the many religious events at the various sattra, people wore all cotton, traditional clothes; very organic looking, and very white. Men wore dhoti, kurta, and a white gomcha wonderfully embroidered with red; women wore the tradition Assamese two piece saris and the Missing tribal mekhla-chador. It was a pleasant sight. And, unlike North Indian crowds, this was a very disciplined gathering, where there was no pushing or shoving even though it was very, very crowded.

The morning after Raas Leela at Kamalabari SattraThe morning after Raas Leela at Kamalabari Sattra

The morning after Raas Leela at Kamalabari SattraThe morning after Raas Leela at Kamalabari SattraThe morning after Raas Leela at Kamalabari Sattra

The morning after Raas Leela at Kamalabari SattraThe morning after Raas Leela at Kamalabari Sattra

The morning after Raas Leela at Kamalabari SattraThe morning after Raas Leela at Kamalabari SattraThe morning after Raas Leela at Kamalabari Sattra

Villages. Majuli has a population of 155,000 of which the Burmese-Mongoloid Mishing tribes are 42%, the Deori and Sonowal are 3%, and Vaishnava Assamese the balance 55%. The Mishing retain their different language and ways of worship, though commonalities grow due to gradually increasing integration with the majority Shaivite culture.

Farming is the predominant occupation, it defines all life; even those who hold a job in government or run an entrepreneurial business work the land to grow food. The most exciting to me, and a striking part of the village layout, were handlooms in almost every home constructed below the house stilts. Handlooms signify employment for tens of millions and a creative occupation to our rural citizens in perpetuity. If only we can wean ourselves away from the false belief that industrial, manufacturing jobs can address our employment and livelihood challenges across our hundreds of thousands of villages. Handlooms fulfil every criteria for our capital poor and populous nation – low capital intensity, not polluting, easily distributed to villages, do not need electricity, provide flexible work times, no demeaning and dehumanizing industrial discipline, and are creative to boot. But our governments, politicians, elite looks the other way, in the direction of their self interest of urban lives and service sector jobs for their children as the panacea. Gandhi, and his prescient bottom-up thinking for the India that is Bharat, remains only on our currency notes.

Rice is the main crop, with many local varieties, in many villages the rice was yet being pounded by hand. There is Komal Chawal that is ready to eat after being soaked in cool water in 30 minutes; and is served as an outstanding dessert at the sattra with yogurt and shakkar (powdered jaggery). I also saw bau dhan – another local variety of rice planted in water logged land, and is ready in 5 months. The ingenuity of the Indian farmer, and the diversity of traditional seed that vary every few kilometers in response to the microclimate, is under threat by a monoculture of white rice – all imported from outside Majuli.

Pigs and chicken keep the village clean, as well as serve as food. Fishing is the key complement to rice and vegetables, and fishermen start their day at 3 AM to. They sell their catch for Rs 300 a kilo, and on a good day they can catch 5 kilo. At times when luck strikes, they catch a single fish that weight 20 kg.

Organic life. I was delighted to visit Bongaon, where street side shops manufacture and sell musical instruments. Then there is Salmora, where I visited potter families multiple times, fascinated with 4 families working together to help each other with the pottery baking on a large communal kiln. They knead the clay with their feet and shape the pottery with their hand, without the potter’s wheel, and beat them into perfect shape with a wooden bat. The baking process uses multiple layers of mud and straw on the pots, a skill and method clearly handed down over hundreds if not thousands of years. Their skill was spellbinding.

The deeply sunburnt boat makers on the banks of the Brahmaputra continue plying the skill of their ancestors, repairing old ferries and building new ones by hand.

Organic life was also visible in the Bishoni (a hand-held fan), made by bhokots at one sattra: made from Baint Gaus and Tamul Gaus (the supari tree). Young monks also worked at making finely constructed garlands for the hundreds of visiting devotees at this busy time, made from slivers of banana stem and leaf. And candle stands made of banana stem pieces, supported by bamboo stands. The ingenuity and native intelligence of a handcrafted world, using naturally self-destructing organic material, is amazingly alive. Village life is organic, in the sense that bamboo is everywhere, on the roads, in the homes, in every aspect of life. Potters yet ply their trade, and terracotta utensils abound. Cycles are ubiquitous.

At the same time, however, the modern hand of industrial life is visible – old timers told me motorcycles and automobiles have grown exponentially in the past 5 years, only a few lucky ones owned any transport then, as have TVs and mobiles; cement lives in communion with bamboo in many village homes, and plastic garbage is visible in the deep interiors. Though there is no industry; there are government jobs for the lucky few, in the small towns the self-employed dominate – blacksmith, barber, vegetable and provision shopkeeper, dhaba owner.

Two questions the taciturn Assamese villager asked me all the time were ”Kaun Department” which when my initial surprise wore off I understood to mean ‘what do you do’. It was easy to say ‘computer’ to which they exclaimed ‘aah’ and I was let off the hook of being just a photographer. The second was the more tradition curiosity across India ‘where you from?’ which typically meant are you from India? looking out of place as I do with my photography equipment and attire.

Impressions. I was welcomed everywhere I went; the cozy boha in a sattra, a bamboo home in the village, or a dhaba in town. While visiting the Mishing villages it was deja vu that empowering women through handlooms is a solution to India’s poverty and economic activity. Two people I met in Majuli are ‘doer’ beacons, one an Israeli and the other a Russian-American - both walking a path that few of us can.

I was quite bowled over by Gili Navon, the activist. A wispy, gentle, passionate Israeli woman, she is a Masters in Community Development who has spent 4 years (off and on) in Majuli, speaks Assamese and Mishing, and travels village to village on a bicycle. A 4 month internship in 2010 turned into a full time passion, and she has now setup an NGO – Amar Majuli - with Bedabratta, a local who runs the Ygdrasill Bamboo Cottage. Thanks to them, I have been able to establish a permanent connect with the handlooms, that will take me back to Majuli time and again.

Then there is Leonid ‘Leo’ Plotkin, the nomadic pilgrim, whose passion for documentary photography and interests in history, religion and mythology mirror mine. Not by chance, the first quote on his web site is from Somerset Maugham “Those who remain at home may grow richer and live more comfortably than those who wander, but I desire neither to live comfortably not to grow rich”. A graduate of leading American Universities (Purdue and Boston), Leo was a corporate lawyer till one day 10 years ago he upped and left that life, at 33. Since, he lives off his dollar savings, and travels the world on his terms. He doesn’t get to meet the elite when he is in India, he travels by local bus and stays in accommodation connecting with the daily life of regular people in the most extraordinary of places. He has seen more of real India, in an up-close manner, than I ever will. More, he lives with less – an ascetic approach to life that only the brave follow. Read his photo essay on Majuli here.

“The scholar does not see the straight path,

Nor does the performer of a million sacrifices attain Hari

Both fall down to earth and anon,

All rites and rituals,

All pilgrimages to Gaya and Kashi

Made round the years,

All yogas done and rhetoric learnt,

Only cloud the vision

Forget therefore the vanity of learning and rites,

And worship at the foot of Hari,

In your innermost soul.”

A bargeet by Sankaradeva