Change

70 years ago, the wealthy commenced flying to Bhuj, the capital of the then principality of Kutch, from Mumbai in 4 hours on an aging Dakota propeller airplane. 125 years back, the intrepid traveller braved two equally difficult options from Mumbai: a 35-hour train and boat combination journey, or a two-day voyage on a slow steamer ship on the choppy Arabian Sea. Further back in time - some 200 years ago, a good 50 years before the first railway was laid in India - it took a traveller ten to twenty days, depending on the weather, to reach Kutch from Mumbai on a local Kutchi boat. And that was the way it was for hundreds, even thousands, of years. No wonder Kutch desh was difficult for outsiders to access, it remained isolated and content in itself.

The death of distance, now buried deep by wireless and communications, has sharply accelerated change in the past 3 decades. It is not coincidental that this was the period that the Indian economy 'opened-up', in 1991. Along with this, the massive earthquake in Kutch in 2001 accelerated ‘development’ through large investments of private capital in mining, petroleum and ports.

I reached Bhuj from Delhi in October 2016 in the comfort of a one-hop jet flight via Mumbai, in what we today would consider as a long domestic journey time (including a layover) of 4 hours. Bhuj is now served by airlines from all over the nation, and Kutch is within easy reach of unsettling modernity. Amitabh Bachchan beckons us for the Rann Utsav, a tourist festival that attracts people in the thousands to an area, and can be booked on-line “no trace of any living creature till the far horizons but come winters and the area transforms into a throbbing city of tents having all modern amenities from AC tents to state of the art dining and activity areas to ATM and mobile towers.” So much for responsible, low-touch cultural tourism that supports existing organic local traditions and livelihoods; it’s the ‘development’ narrative. What more could one expect.

In the headlong rush to make money in which we all are complicit, there are signs everywhere that society embraces change remorselessly; destroying all elements of the past and building a shallow, plastic present. Greed harnessed to globalized private capital; technology; and nation-states distributing patronage and consolidating power are too powerful a coalition for the simple, skilled handloom and handcraft worker in the village.

There indeed were elements of the past in Kutch that needed to be swept away by change. To name the most distasteful - there was an active slave trade, from before the British; the terrible Rajput customs of infanticide where the girl child’s life was ended before it could begin; and Sati, the unique custom of the ‘voluntary’ burning of the widow on the pyre of the dead husband. “In 1842, the ratio of Jadeja girls to boys was as low as one in eight” and the custom became widespread across all castes.

From the 1842 British Gazetteer “The child’s life was generally taken by giving it opium, or it was smothered by drawing the umbilical cord over the face, or it was left to die of weakness or want of care. When a girl was born the father as seldom told, all he heard was that his wife had delivered and that the child was in heaven. On this he bathed and nothing more was said. Sometimes the mother refused to take the babe’s life. Then the father was called and unless, which was rare, his heart softened, he vowed neither to enter the house not eat till the child was dead. Shrinking from it at first, women soon approved of the custom and when old were keener than the men that no girl’s life should be spared”. Kachchh The Last Frontier, by TS Randhawa, 1998.

Many aspect of change needs to be accelerated even today - child marriage continues to be prevalent, though decreasing as education permeates; the provision of education and health care remains abysmal, and what is available is erratic in reach to those who need it the most. This is the story across our very poor and yet predominantly rural nation, though I am hard pressed to have urban friends believe this reality ready as the are to believe in the destiny of India as a once more powerful nation. But I digress.

What causes me consternation in rural India is not so much change itself, but the mindless destruction of traditional livelihoods by deployment of capital to inappropriate industry, and the intimate relationship of this with the rapid and visible deterioration of our environment.

Across rural and mofussil India, specially in unique areas like Kutch with a stunningly powerful heritage of amazing crafts, skills and natural materials, modernity has decimated livelihoods and impoverished communities that depended on skills and materials developed over millennia. Tens of millions of livelihoods have been destroyed by modernity at an unprecedented pace, the impact of which is yet to fully play out even as we see the slow-mo pan out in front of our eyes. The handful of manufacturing and service jobs that have taken their place have no opportunity for the displaced hand workers, who are added to the growing millions of casual labor at construction sites, or to the masses of the jobless. Sounds terrible, but yes that is the reality. Some of us, perhaps, would do something about it if we were to accept this truth.

Kutch

I couldn’t have found a more accommodative and helpful host than the 40-something Krutarthsinh Jadeja at the village of Devpur an hour to the west of Bhuj. He knows his home state well and he proposed an itinerary that became the starting point for my planning, put his vehicle and driver at my disposal, and introduced me to young Kutchi's Samir Bhatt and Salim Wazir. This Brahmin and Muslim youth are symbolic to me of a happy co-existence, of the potential of Indian diversity, and the possibilities of living together in our differences. I witnessed the enormous diversity of the people, ecology, crafts and religions of Kutch in their warm presence.

One of the largest districts in India, over 46,000 kilometers but with only 2 million people, Kutch is a virtual island and was physically isolated from the rest of India till a bridge in the east connected it to Kathiawar. Kutch is geographically connected to Sindh through the Rann of Kutch in the north, which explains its close cultural affinity with Sindh through ethnicity, customs, clothes, language and music. Sindh, Kutch and Saurashtra were a cultural continuum from times immemorial till 1947; a shame that a ‘hard’ man-made barrier has closed all symbiotic exchange between what is the same people.

The Kutchi ecology is wonderfully varied, with low hills and ravines, desert, marshlands, grasslands, mangrove swamps, salt-pans, and plains; but the people in Kutch are a true delight, with varied races, religions, communities and cultural traditions intermingling and co-existing. In October, the weather was cool in the morning with a hot sun through the day; the rains had been poor this year and the landscape was not a green as it should be.

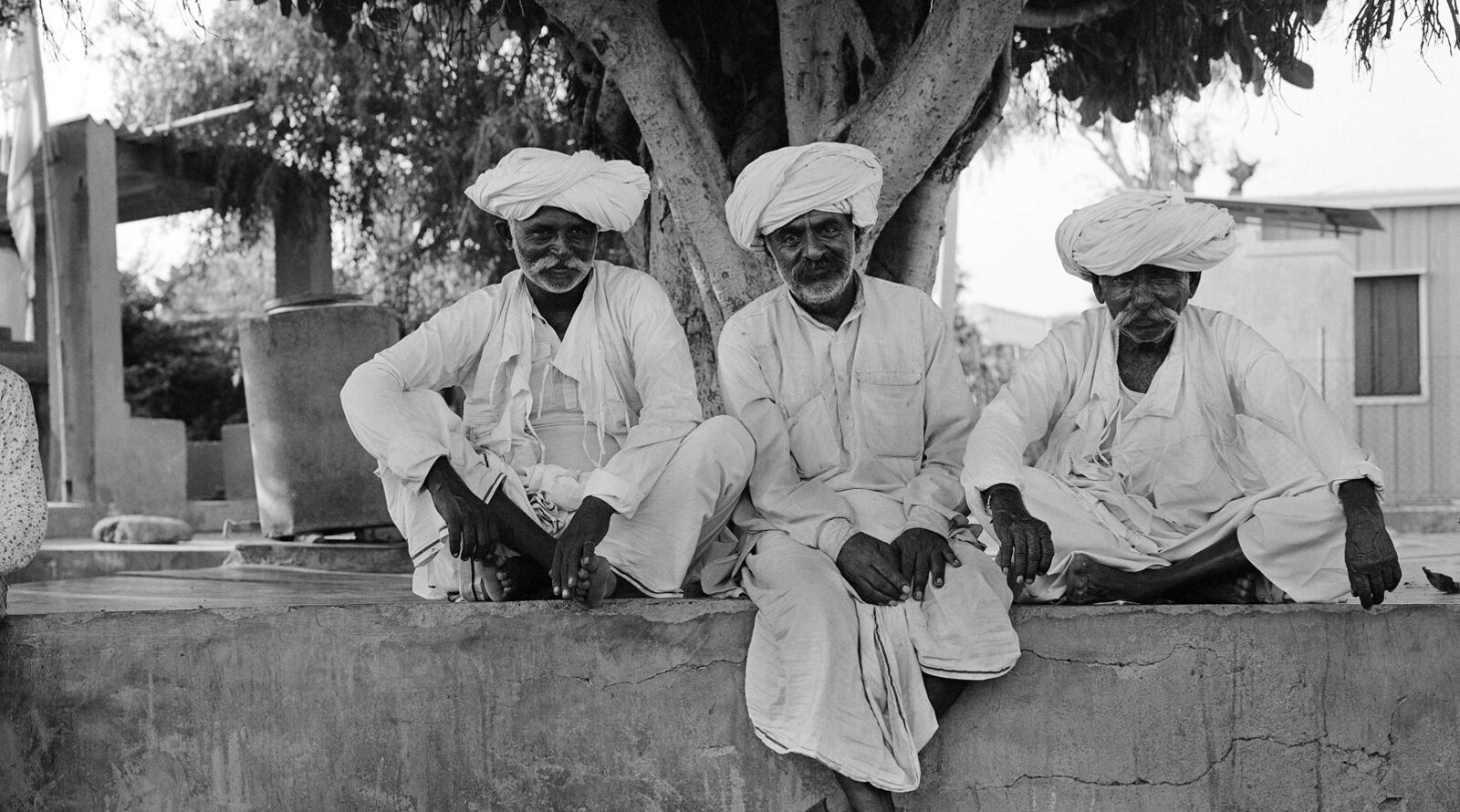

The Rajputs of the Jadeja clan remain at the top of the social totem pole. They ruled Kutch for over 500 years, with a history of accumulation of wealth, land, and of feudalism with all its baggage. Kutch has a 65% rural population, pastoralists (nomadic, semi-nomadic people with sheep, cow and buffalo) called ‘maaldhari’ (maal being wealth) forming the dominant culture in the region. The largest pastoralist group is the Rabaari (Hindu) cattle-breeders and shepherds; I witnessed older menfolk yet enjoying being out in the open and sleeping under the open sky than in the cemented village home. The second largest among the pastoralists are the more than 24 varied Muslim groups who trace their ancestry to Sindh, now in Pakistan – the largest of these are the hardy juth (no connection with the agriculturist Jat of the North West Indian plains, or is there something lost in the mists of time?) who live with their cattle in the 1,600 square kilometer Banni grasslands. I also learnt there are more than 80 endogamous Muslim castes and groups (zaat) in Kutch, all more or less at the same social level, while the urban Muslims (Memons, Bohras, Khojas and others) inhabit their own spaces and are mostly cut off from their rural co-religionists.

The Ahirs and Patels are dominant amongst the settled agricultural groups in Kutch with large land holdings, once rural they are now increasingly urbanized; each with scores of endogamous sub-clans. Then there is the head spinning kaleidoscope of other castes and craftspeople that had once kept alive the once-rich tradition of hand crafts in the villages: khatri (block printers), kumbhars (potters), suthars (carpenters), sonis (goldsmiths), kamangars (painters), vanjas (silk weavers), wankars (weavers), meghwals (leather workers), kansaras (coppersmiths), lohars (blacksmiths), wadas (lacquer workers) and many more. All these varied community identities are surprisingly the source of some comfort, as you will see later. I’ve not seen crafts of this depth and width in too many parts of India, and Kutch is unique in the widespread nature of its handcrafted traditions. I suspect, though, the Indian village would have been an interdependent and organic whole acoss much of India before the economy was devastated by British self-centered resource extraction, and trade and industrial policies in the 19th century.

The banni and the Rann are remote even today, but no longer inaccessible. Till 1980 most people here hadn't ever seen a car, now many possess a motorcycle. The last 15 years, since the massive 2001 earthquake in Bhuj, have seen significant investment in infrastructure: there are, for example, better roads, electricity, water access, and schools. There is new industry due to the SEZ tax breaks next to Mundra port; a new Tata-owned power plant, large corporations like Suzlon and Welspun and jobs for the educated qualified. A murmur of discontent reached me though - people who sold land, or were forced to give up land, for SEZ acquisition now repent selling it.

Ahir

We visited Dhaneti village of 5,000 of the dominant Jadeja and Ahir castes who together own most of the land, and the pastoralist Rabaari; we had lunch with prosperous Ahir Maojibhai Chhanga who farms 70 acres. He is a much travelled and worldly-wise farmer, growing food organically for home consumption on 1 acre with the rest fully chemical-fed for the market: wheat, jawar, bajra, dhania, jeera, castor, moong, peanuts, cotton and sesame. His water boring is at 700 feet, with the water level currently at 300 feet; water problems for farmers are immense as these levels dip each year. Maojibhai was a mason for 20 years in Bahrain (which explained his this-worldliness); his eldest son is employed as a teacher in the village, and his younger one farms the land after having spent 10 years in South Africa. They travel, these Kutchis. He recounted (to impress) how he knows an Important Man, a government official who has 4 gunmen with Machine Guns. His prestige was enhanced in the entire village Ahir community when the Important Man and his gunmen came home for dinner, everyone in the village came to know.

All weddings take place within the village, but with very defined gotra: for example, the Chhanga weds only the Dila. Other Ahir gotras are Mata, Dangar and Patel. Ahir children, he said, are studying now but “not much”. The schools are not in good shape, both government and private. I wasn’t focused on investigating this aspect in Kutch, buy it couldn’t be very different from the rest of the country where standards of all levels of school education remain generally abysmal.

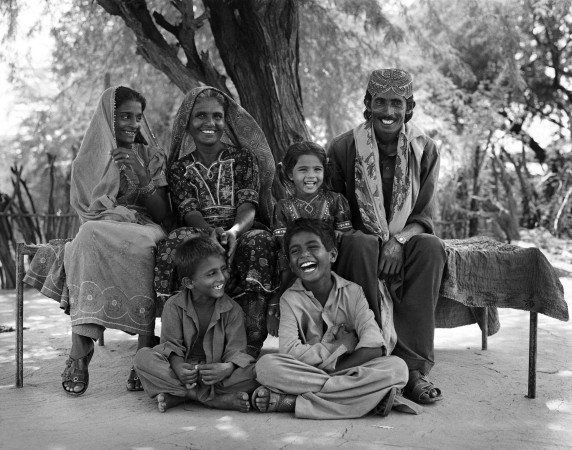

His life seemed well structured and organised, and his hospitality fantastic – as I experienced in every Kutchi home I had the good fortune to visit with Samir and Salim. His wife and daughter-in-law plied us with large Bajra rotlas dripping with ghee, sabzi, rice pulao, a chutney of red chilli-dhania powder-jeera powder-lehsun, and the ubiquitous chaach. There was simply no way to explain my vegan-ness and low-fat nutrition in front of their warm giving, I just had to enjoy it all. And I did.

Rabaari

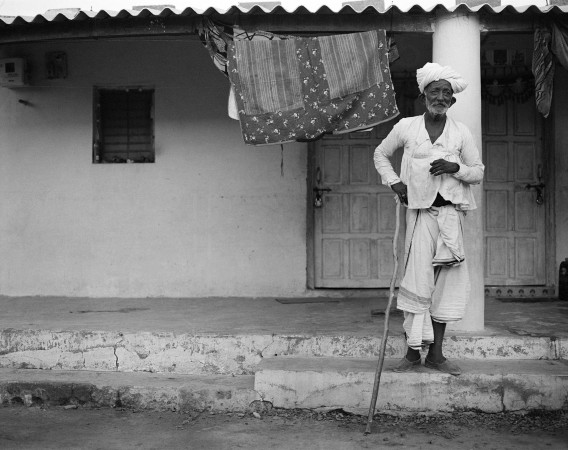

In the cooler evening, we visited the Debariya Rabaari village of Maringna. This was so very different from the settled Ahir way of life – the older men were sitting around with the goats and cattle, smoking the hookah, or were seated around the big village square tree shooting the breeze. The men and the youth were out herding, and the women were making Sukhdi – a delicacy made with heated ghee, lots of jaggery, and wheat flour. In between gossiping and fending off children wanting to dip in, the beautifully-clad women and young girls spread the semi-solid mixture on a thali, and cut it in pieces for storing. Some were making Matr with soonth as energy snacks for a new mother; while the older women sat around and clucked over the mother and newborn. As I strolled around, one of the old men with a leather-beaten face and traditional white clothes and pagri asked me “Aapke des mein Modi aaya? Aisa aadmi nahin dekya!” I couldn’t agree with him more, though for very different reasons. I loved his reference to des – clearly, Kutch is yet a separate nation for some of the older generation. How nationalism changes in the era of the nation state, and how it changes us.

The next morning, we left early for the grassland Banni area in north Kutch. As we sped from Devpur through the city of Bhuj, we went past roadsides strewn with plastic detritus everywhere till the eye could see. While the visible problem is an inadequate system for segregation and collection of waste, the real cause is the modern economy we live in that produces massive quantities of non-biodegradable waste that grows exponentially in line with our commitment to ‘development’. Swacch Bharat has to become more than a slogan if it is to succeed, even in Modi’s Gujarat.

As we headed to the Banni, we went past many kilometers of the terrible folly of an ignorant bureaucracy – the Prosopis Juliflora or Mexican mesquite, known locally as Ganda Babal or the “crazy tree”. Planted during the times of the British to supposedly green the desert, this invasive and hardy shrub has colonized and overwhelmed the local ecosystem. I have seen this in Western UP, Rajasthan and my native Haryana (we call it Vilayati Kikar), and was surprised to see it thrive in far away Kutch. Instead of grasslands, we could only see this crazy tree. Local folklore says the massive 1819 earthquake changed the flow of the Indus River and the Rann of Kutch was formed; the rich grasslands disappeared over time, though even now after rain there is lots of grass and it supports many tens of thousands of cattle and buffalo.

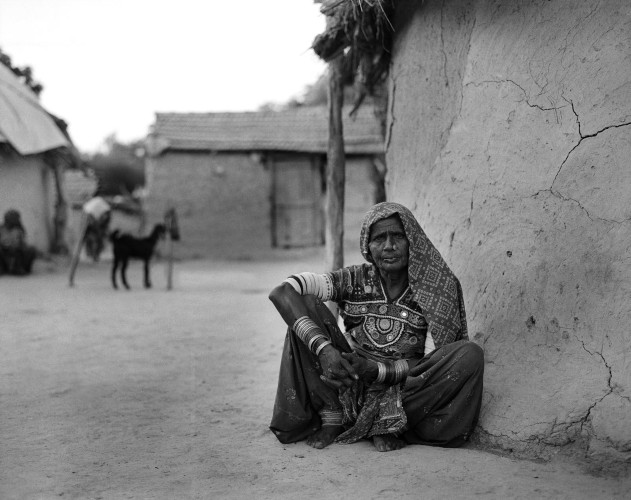

At Gadha village, we met the sarpanch Devsi Ladha Rabaari, another mobile Kutchi who spent 9 years in Dubai as mason, canteen owner and a driver. Now back home with his nest egg, he has done well for himself and practices settled village agriculture, and rears cows, sheep and goats. Unlike the Ahirs we met earlier, he is emphatic about his gotra not marrying within the village and confidently shares that Rabaaris have 118 gotras across India. We stroll around and get an opportunity to speak with 51-year-old Valu Behn Rabaari. She tells us all – and that means all - money earned by her son and husband as salary is given to her at the beginning of the month and when they need they ask money for their expenses. This is an unusual tradition of Rabaari women managing home finances and home affairs independently: the men traditionally spent time away managing the sheep, goats and cattle and had no time for home. While the pastoral life-rhythm has changed, families continue to empower women. What was even better was that there is no alcohol in the village at all, and no violence at all in the marriage in the Rabaari. I wished this all were true, and I had no reason to believe it isn’t.

Pathan

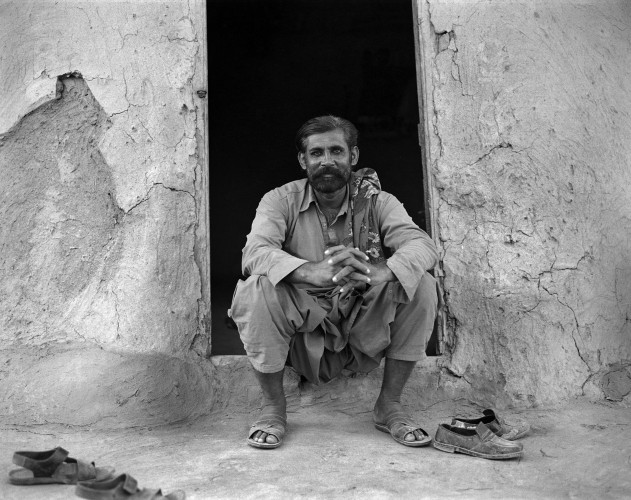

We spent most of a day at Zararwadi, a compact Pathan village, where Salim has long-standing relationships. This settlement of 15 families was impoverished and living on subsistence, which did not in any way come in the way of their very warm and friendly welcome. The villagers live in simple and clean mud homes with reed roofs, Bungas – exactly what rural Haryana and UP calls similar looking huts in which hay for cattle is stored, indicating the common etymology of names. Their livelihood comes from multiple sources of which the most important is Chhota Maal, sheep and goats; they also tap the Acacia trees to collect Gum Arabic; collect honey; charcoal; and grow some Guar lentil. I witnessed the process used to make charcoal from Prosopis, which they sell in the city for modest amounts nowhere in proportion to the laborious efforts they invest. Here, deep in the banni, I saw some original flora that has escaped the Prosopis - Meetha Neem and Desi Babool.

The Pathans were on the losing end of a land conflict with their neighboring village - populated by the more powerful and prosperous Halepotra - for access to land that can be used for grazing of their goats and sheep. This conflict impacts their livelihoods and colors their daily tribulations as it is of central importance to them; school does not really figure anywhere in their scheme of things. That they remain so welcoming and warm was a joy to witness.

We lunched at sarpanch Salam Halepotra’s Mehfil-e-Rann in Hodka village, an absolutely wonderful home-like meal, wholesome and tasty. Salam looks like, and is, a sharp entrepreneurial man, and has constructed a number of rooms in the traditional bunga style where visitors can spend the night. There are others with the same idea – Umra Kana Meghwal has a similar set of 7 bunga desert ‘resort’, where he charges Rs. 3,500 a night for 2 people including all (home cooked) meals and folk music to boot. The Rann is magical then, silent under the clear skies and millions of stars, and the quiet, unending stretch of the land as it meets the horizon.

There is enhanced pressure on the local culture due to massive increase in tourism over the past decade, a story one sees repeated across India, and with this comes the destruction of the rich local culture and a challenge to the community to preserve those elements that makes then unique and why tourists visit in the first place. What is responsible tourism, and how can it be undertaken in an environment where every local is desperate for livelihood? What is the role of the government? Of local entrepreneurs? Of tourists? The government sponsored annual Rann Festival, for example, has put Kutch on the tourist circuit ’map’ and created infrastructure; it has also brought in a massive rush of tourists many of whom couldn’t care less for the preservation of the local culture and who go back after a 3 night stay in an artificially created ‘village’. The ugly tourist is omnipresent.

Juth

Salim was hesitant to have me visit the Juths as they don’t welcome guests any more. The world beats its way to their doorsteps because their appearance and way of living are so striking, their men gauntly handsome, their women stunningly beautiful and their fast disappearing pastoral life so different from anything the settled urban human knows. With the advent of digital and cellphone photography, a photographer is terribly invasive and not at all welcome. The Juths are a conservative lot, and in any case who wants to feel examined under a lens. This unease of the representation of women that was uppermost in the minds of all the communities I came across is rooted in the manner their images have been ‘used’ – by government, tourists, and entrepreneurs – to showcase exotic Kutch. How could I escape this conundrum, no matter how much I remained sensitive to it.

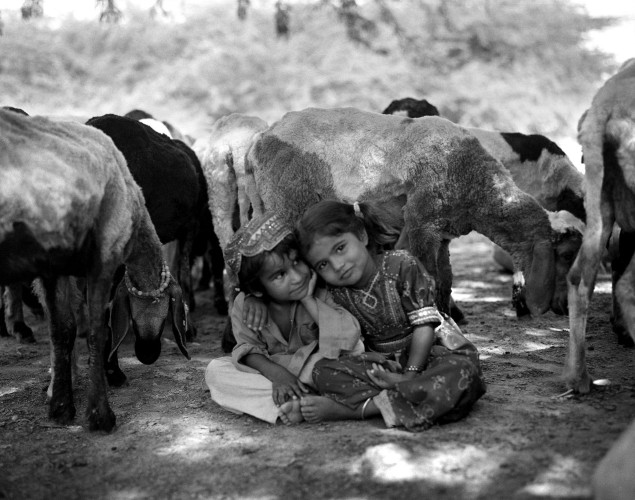

The Juths are comprised of three endogamous clans: the Dhaneta (cattle herders), Fakirani (more traditional), and Garasia (with garas = land). We drove to Bagaria village of the Dhaneta, 60 minutes on a dirt road north towards the White Rann, past 17 kms of tall Kal grasslands that looked like we were in the Africa savannah. The slow drive was ethereal, going past a vast open landscape on both sides unlike anything that I had seen before, with the anticipation of witnessing something very different. We took along two Ahirs from a nearby Vanya village who have a close relationship with the Dhaneta (their buffaloes are outsourced to the Jaths: read this interesting story on the hardy Banni buffalo in 'Down To Earth' magazine), they too tell me there are no divisive religious differences in Kutch.

To the photographer in me, the village was a let down - first, because we had reached close to dusk, then the men squatting around in the square were singularly unexceptional in their salwar kameez, and we weren’t welcomed or encouraged to walk around or indeed asked to come back another day for an exchange. They wre a suspicious lot, happy in their isolation and I understood at one level. The ride back, though, was as inspiring as the ride in. Somewhere along the way, we gave a ride to two pensive men. Rabaari men who in rapid fire Kutchi shared with us how they had lost two camels some days ago, and were tracking them. My heart went out to these two worried maaldharis as I saw them get off in (what looked to me) the middle of nowhere, and walk into the darkening horizon in search of camels in a desert.

We discussed why men don't wear traditional clothes any longer, and one of them said “when they do, they don't get respect in the city as they are considered villagers. Pants and shorts are considered progress, that is why fabric and tailors are rarer now. Soch badal gayii.”

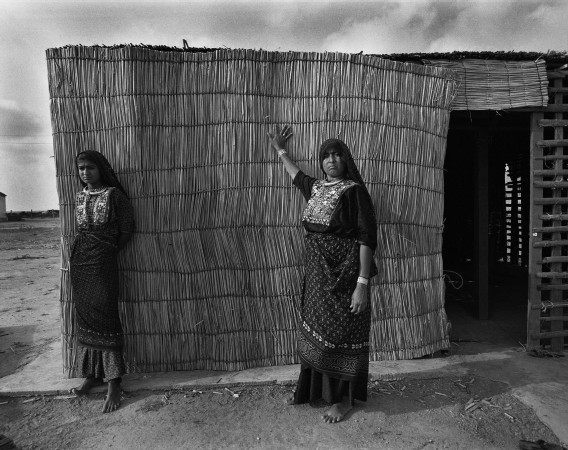

We spent time at the Fakirani Juth settlement of Dragahwand, a village of 60 people where we met Nani, a confident and outspoken woman with a point of view. We watched women and girls constructing a home, a 'Pakha', while Nani explained how she has been associated with two NGOs working with their community. Both, however, seem to be concerned with talking than doing something that establishes sustainable livelihoods.

We stopped at the home of Hasan Kumbhar at the nondescript Lodai village. A National award winner from 1991, Hasan is the only living representative of his community’s traditional skills of mud pottery, the colors and design yet very connected to the Harappan civilisation.

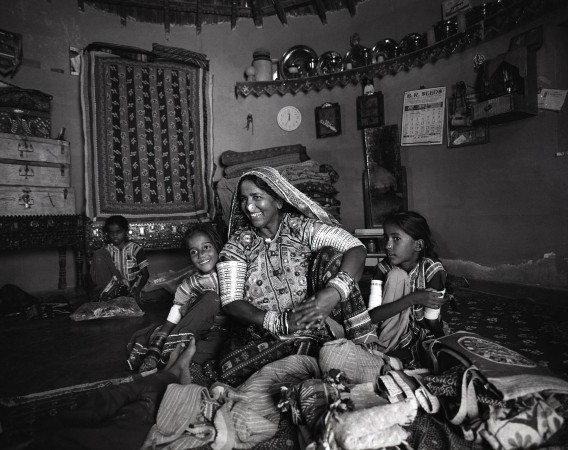

Meghwal

We reached Ludiya village, in a community of Marwara Meghwal Harijans (this is Gandhi land, and I can only guess that is why they still aren’t called dalits as elsewhere) of stunning beauty and craft; certainly one of the cleanest villages I’ve seen in India. I am convinced the cleanliness has a lot to do with the absence of water flowing along the streets in open drains, a hallmark of northern villages. The village was clean without any visible plastic or shops, each home had everyone involved in and contributing to livelihoods: bharat embroidery for clothes, wallets, purses, bags; wooden carvings and doors, furniture. Each home was beautiful, the mirror work and colors breathtaking; the thick mud walls and mud floor providing a cool haven from the heat outside. All the residents were gently welcoming as we walked around, eager to show what they had. The so-clean temple with an equally clean surrounding is dedicated to Ramdev Pir, an avatar of Sri Ram. We attended the twilight prayer ceremony; magical with the temple bell being struck by each of the congregation, the soothing aarti, and the prasad. An old lady repeats age-old wisdom “the name is Allah or Bhagwan, but he is the same”.

We had dinner at Khajju Bhai Kaka's bunga: rotlas with ghee too many to count, chaach, sweet rice (elaichi, saunf, sugar, ghee) and the most amazing aaloo sabzi I’ve ever eaten. We were a strange quartet: a Brahmin, a Sunni mussalman, a Meghwal Harijan, and a non-believer; sharing a vegetarian village home meal sitting on the ground.

Lying after dinner on the charpoy in the open under two Neem trees silhouetted against the half moon, no sounds of the modern world intruded, just Kutchi voices carrying across the banni, cool wind in my face, clear sky and millions of stars above, and not a worry in my head. I knew instantly this was one of those rare moments of contentedness, my faith in humankind rekindled by coming face-to-face with gentleness, kindness, acceptance, beauty, and diversity. The possibility of India teaching the world co-existence came alive once again in my mind, if Indians are willing to learn lessons from micro-spaces like Kutch.

Religion

Besides the industry and cheerful demeanor of its adventurous and enterprising people, Gujarat is also known for fractured communal relations between the Hindu majority and the Muslims who form 9% of the population.

In Kutch though, with a Muslim population of 21%, no tension exists.

I learnt that, while there are the usual fringes with an extreme ideology on both sides, there has not been any communal violence since Partition, during the massive 1969 riots in Gujarat, and not even during the violence in Godhra and its aftermath in 2002. Muslims and Hindus continue to be invited to each other’s festivals and weddings where vegetarian food is served separately; and there isn’t any restriction on Muslims eating at Hindu homes other than I would guess the very traditional urban upper castes. I accompanied Salim to an Ahir temple festival, and we both ate at a meal in the Narayan Sarover temple kitchen without any sense of unease. Cross-worship at temples and Sufi shrines is widespread, with none of the communal virus that has deeply infected parts of Gujarat, and there is a general atmosphere of comfortable co-existence. The number of such places is clearly rapidly shrinking, bu I was happy to be in one.

The administration is vigilant, and I witnessed a well-protected Moharram procession in Bhuj – the revelers looked like they were enjoying the event, what is most parts of Shia Muslim world is a sorrowful day of the martyrdom of their Imam fighting against the forces of Sunni tyranny. Maybe the Kutchi are truly less serious about themselves than their Shia brethren elsewhere in India, which is altogether a good thing. Hindutva as a mobiliser of extremist communal feelings is stronger in the Jadeja and the Patels, and even within the rural Muslims there are visible strains of a more mainstream and hence conservative practicing of Islam – par for the course in the rest of India.

One reason for the peace could be that the pastoralists, the largest group among the Muslim community with scores of endogamous sub-groups within, are concentrated in isolated, homogenous villages in the rural and remote northern part of the district, in a physically extremely demanding ecology. Perhaps the sense of a historically strong Kutchi identity (with the Kutchi language playing a significant part - the language drawing more from Sindhi than from Gujarati) and has led to a more integrated society; which together create commonalities at the intersections with Hindu rural communities. Pastoralism is yet another powerful link that establishes bonds with Hindu groups of a shared way of life, of a common harsh existence in which the challenges of survival at the margins and the struggle with nature far outweighs the differences in religious beliefs and customs. It seemed to me that the strong identification with their own group or clan – say, the Fakirani Juths or the Rabaari - around its well established way of life and culture is so powerful that the larger religious identity of Islam or Hindu is not the primary means of communal solidarity.

Read this wonderful 2008 piece by Yoginder Sikand for an insight into the world of the rural Kutchi Muslim. Randhawa writes in his 1998 book Kachchh, The Last Frontier “this openness to all religious faiths goes back to the common roots of the Jadejas and the Sammas of Sindh … The Kachchh rulers paid equal reverence at temples, mosques and dargahs; though being Hindu, a good portion of their army was Muslim”. Krutarthsinh’s ancestors gifted the mosque in Devpur, and contributed with generosity to Dargahs and Pirs. On the Ashura of Moharram, the Tazia procession stops outside the Jadeja darbargarh and Krutarthsinh comes out to meet it to offer flowers. I witnessed Moharram events and Navaratri celebrations, one following the other, at the Devpur village Chowk.

A heterodox mixture of saints captured the imagination of the people by their ascetic lives, and myths around their lives marks popular worship that centers around shrines that possess both fame and riches today in direct proportion to the distance the master kept away from both in his lifetime. There are temples, mosques and dargahs by the hundreds, with some co-frequented by peoples of both religions and certainly respected by all.

While dropping me to the airport on my way home, Sattubha, Krutarthsingh’s loyal clansman and driver, said “95% of Muslims are regular people like us, but every community there are black sheep; in the Muslims, there are a minuscule minority who support Pakistan and create trouble.” A hint of the nationalism based on the aversion to Pakistan, but it doesn’t translate to a burden of proof on the Kutchi Muslim.

Music

We met with Bharmal Sanjot Meghwal at the NGO Kala Varso Trust in Bhuj, working for the last 15 years with Kutchi musicians. Here is a very deeply contemplative and tranquil documentary “So Heddan So Hoddan” (Like Here Like There). Structured around the life of the Fakirani Juths, the documentary exposes us to the poetry of the 17th century Sindhi Sufi poet Shah Abdul Latif Bhitai and the bardic myths of ‘unfulfiled love’ of Marui and Umar, Sasui and Punhu, and others as a metaphor for life. Only one man in Kutch Usman Sonu Juth now plays the melodiously haunting 5-stringed Surando, a Sarangi-like instrument.

“Crafted intricately, the base of the stringed instrument Surando is fashioned from a single piece of wood to create the most precise shape and perfect melody … Over the years the charming sounds of the Surando whose bow is strung with the tail of a horse have been silently disappearing in the vastness of the Kutch lands. Osman Jat is the last known master of this instrument and as he strums his deft fingers across the strings, this quaint art of creating music which he acquired from his forefathers is brought to life but unfortunately might soon be extinct.” http://www.dekulture.com/d-11-14-surando-instrument.php

Usman is, I was told, a full time truck owner-driver often on the road making a living, and plays the Surando only when he can take time off, often to the accompaniment of his cousin Mustafa Ali Jath’s singing and the encouragement of self-taught Sufi cousin Umar Haji Suleiman. “ …दुनिया ग़म के ख़ज़ाने में भरी पड़ी है .... अगर मुसीबत को बरदाश्त कर गया, तो समझ लो इंसान बन गया”.

Bharmal is connected to Meghwal and Bhil musicians who sing the Aradivani - Kabir, Mira, and others – on the santaar, manjira and gado. And there is the evergreen Sufi kalam from Bhulle Shah on the harmonium, dhanjari, dholak, banjo.

Later that day we visited Biriyandiyara village, in a community of the Marwara Meghwal. We met the smiling and energetic Dana Bharmal as he came out of his home speckled with limestone splashes, paintbrush in hand. He didn’t need too much encouragement to transform from painter to a musician, ducking back in and coming out all dressed and with his gamela, manjeera and gado. It was quite amazing that he was completely self-taught, and now sings for local Kutchi events and tourists - we listened spellbound to him and his little son, a perfect picture of art in the village.

On the way back, we bought Mava (crudely, milk cake) from the Sarhad Mava Center that sold just this and tea. Made from cooked and thickened buffalo milk, lots of sugar, and elaichi, it is famous all over Kutch. We dug in.

I looked for cotton prints to take home, with the beautiful flower designs of the kind I had seen women of various rural communities wearing, and was stunned to discover that these fabrics are synthetic. Not believing people in this terribly hot weather could wear synthetic all year around, I looked through shops all over the Bhuj market and was left disappointed. The tail wags the dog – people wear what the factories in Maharashtra and elsewhere produce, as synthetics are cheaper and longer lasting they are welcomed, despite the discomfort. Here lies buried the story of how modernity has demolished cotton handloom, and synthetic reings over organic in ways more than one.

Devpur

Krutarthsinh runs an atmospheric 6-room homestay in his 1905 built ancestral home built in sleepy Devpur, where he also manages a much-respected high school. I stayed in a lovingly restored room with traditional wooden-beam roofs, jharokas, and limestone-plastered walls – a world away from the tourist world, deeply immersing me in the local ethos. What was truly engaging was Krutarth’s personal caring, and his old-world hospitality. We engaged over many dinners on how he started the homestay by chance, how he restored old rooms, his getting used to running it as a business; the school, his late father, and his unusual guruji. He came across as a self-aware man, steeped in Kutchi tradition, and world-aware.

Reminiscing the small effects of modernity, he shared the story of a Rabaari mother who works at the school. She brought her daughter to him for resolution of a minor dispute: the child wanting to wear a salwar kameez instead of the traditional Kutchi dress now increasingly going out of fashion.

One early morning, Krutarthsinh and I strolled through his 12-acre organic orchard of mango trees interspersed with ber, nimbu and chickoo. He had just completed building a two-room tourist lodge here, with plans to install 5 tents with open showers. Here was a man with an environmental and community conscience – the rooms were constructed with bricks made of 90% yellow stone dust and only 10% cement; the open air baths were stunning; and the actual work was undertaken by a Bhuj-based vocational training organisation (also supported by him) that trains young boys in basic skills like masonry, electrician and plumbing.

We discussed communal harmony in Kutch, how he feels it is due to the regions general ability to live with each other. The Kutch Jadeja kingdom was for centuries sandwiched between two powerful Muslim-ruled neighbors - Sind and Ahmedabad - so there was a desire to co-exist than be in conflict. There is a trickle of Sindhi Hindus who migrate to Kutch even today, fleeing religious intolerance in Pakistan, which feeds prejudice in some Kutchi circles; but nothing more.

The afternoon I was to leave for the airport, Salim invited me to have lunch at the Wazir residence in Bhuj. His father, the senior Wazir, is the pre-eminent collector and connoisseur of Kutchi textiles; though the most precious gift he passes to his children is his fluid gentleness and calmness. We had spent many pleasant moments over the past week discussing Shia-Sunni relations, Kutchi handlooms, and more. This occasion was a feast of bajra mutho, dal, aloo, roti with ghee, chaas and fruits. We sat in a circle on the ground – the Wazirs, myself, Sattubha the rajput car driver from Devpur, and Samir the brahmin amateur photographer and guide – and enjoyed a memorable vegetarian meal. They had perhaps been stumped for a bit with my vegetarianism, but put out a feast that I will long remember for much more than the food.

Questions Remain

How can tradition thrive within modernity? Do traditional livelihoods for the many have to give way for modern livelihoods for a few? Can an organic life co-exist with human greed? Isn’t development of industry and destruction of the environment two sides of the same coin? Isn’t a clean rural village better than a crowded, polluted city; but then what about caste? Is change one mass that has to be taken as an indivisible bitter pill; is there a chance of choosing from what is nurturing and what is destructive? But then, who chooses for whom? Is tourism any good at all, and when is it not? If co-existence is possible in Kutch, is there hope for the rest of us?

These complicated questions ricochet as I reflect on the 10 wonderful days I spent in Kutch. The answers are terribly inconvenient to the way I live, and clearly not to be discussed in the living rooms of Delhi homes.