Rural Bikaner

Rural Bikaner

The districts of West UP and Haryana surrounding Delhi are amongst the most densely populated and heavily cultivated places on earth. Our runaway population is increasingly settled in a never-ending series of small and big mechanised towns merging into each other and into the megapolis of Delhi. The vastness of the desert is therefore exhilarating after the suffocating weight of human civilisation of the Ganga-Jamuna plains. Travelling in rural Bikaner was liberating, especially in these times, the 360 degrees expanse of horizon enabling one breathe with relief and surprise. The urban eyes initially cannot believe this landscape stripped of people, buildings, roads, vehicles and machines. There are far fewer humans in the towns and villages, the desert radiates a meditative silence, villages lanes seem deserted and the dhanis (thatched huts of peasants located in agricultural fields, away from the settled village) at a healthy distance from each other establish a sense of quiet, self-sufficient isolation. Camels in the dunes and fields add a phlegmatic element to an already majestic ecology.

There are few areas left in India where agriculture is currently practiced as it was before the advent of the (ill-named) ‘Green Revolution’. The decades after 1966 brought about a rapid increase in productivity of the mono-cultures of rice and wheat crops in the North West states of Punjab, Haryana and Western Uttar Pradesh. Along with this, however, piggybacked excess irrigation through the extraction and over-exploitation of ancient underground water aquifers and the application of fossil-fuel based chemical fertilisers and pesticides that are slowly and surely destroying our soil, water and health. Why not call this what it now clearly know it to be - chemical agriculture. The promise of food sufficiency was realised, with costs that we are yet to fully assimilate spiritually, intellectually and physically.

One can find ‘natural farming’ only where Man is yet constrained by Nature and the gods – as in parts of arid rural Rajasthan. Here too the enterprise of some traditional farming castes has brought about unhealthy shifts in cropping patterns since the 1990s – borewells to 1,000 feet and beyond have been dug for vast sums of money and millions of litres of water is pumped from deep aquifers into ecologically disastrous fields of kanak, chana, isabgol, sarson, jeera, methi and moongphali all of which bring the cash wealth we all so desire. I saw financial prosperity in small towns that has come from these chemically-grown cash crops – cars, two-wheelers and traffic jams in the place of camel Gaddas, and permanent concrete homes that have all but replaced the traditional thatched Dhanis. A very few realise, with increasing trepidation, that the costs for the ecology, culture and human health will be heavy. This realisation, though, is smothered by the distracting pleasures that modernity so easily provides.

I set out to discover and learn from peasants near Siyana and Meghasar villages whose cash-poverty and the challenging harshness of Prakriti has not yet enabled unleash the forces of chemical agriculture and who yet farm these arid lands in the ways of their ancestors. My semi-arid 2.7 acre farm in South Haryana is separated from Rajasthan only by the Aravalli mountain ranges and possesses a similar ecology, though all vestiges of traditional agriculture have been obliterated by the chemical juggernaut. I had much to learn.

Sonaram Meghwal and his family are the precious gems who provided insight to how peasants in many parts of North West India, and across the national border in Sindh and Punjab, farmed in the millennia before chemical agriculture became the norm. The crops grown by Sonaram today are not necessarily the ones that were grown in Punjab, West UP and Haryana till the 1970s though there is a significant overlap. What stands out is the principle of locally appropriate cereals, lentils, oilseeds as food crops, and people living in natural harmony with the ecology. Sonaram practices Chaumasa farming ( Chau four, Masa months of Sawan, Bhadon, Kwarand Kartik), a tried-and-tested method as old as human agricultural settlement in the sub-continent. Life was dependant solely on the monsoon rains, and Man took advantage of the bounty of Prakriti commencing in July each year to sow and see the land turn green and celebrate the harvesting. The summer was not really a problem, as the anticipation of the rains was by itself liberating from the oppressive heat. The food, festivals, clothes and culture formed an integrated whole with settled and pastoral agriculture at the center. There was sufficient down time in the rest of the eight months, with animals tended, organic homes maintained. There was a life rhythm in tune with nature, will all its harshness.

Sonaram has 25 bighas of land, and his multi-crop planting commences with vigour immediately after the first rains in mid-July. The food crops he sows – Gwar (cluster beans), Moth (Turkish Gram), Bajri (Pearl Millet) and Til (Sesame) - are a source of complete nutrition replete with carbohydrates, protein, fat and all kinds of other micro and macro nutrients science does not yet know about. Whatever is the excess from his family’s consumption, he sells. Combined with milk from domesticated animals, it is as wholesome as only real food can get. Til is sprinkled in the Bajri fields, and seeds of the ground creeper Mathira (watermelon, or kharbooza) and Kakiriya, a kheera (cucumber) like vegetable, are sown mixed with the Moth and Gwar fields. Fresh Kakiriya is eaten cooked, and then dried in the sun to be used throughout the year. The protein-rich Sangri came from the ubiquitous leguminous Khejri tree, dried and stored for the year. Humans made this arid ecology nutritious, and lived a religious life in worship of Prakriti. They did not ‘conquer’ nature, they lived in its alternatingly comforting and harsh shadow. 100 grams or a handful of Til seeds produce 200 kilos over his 25 bighas.

65 year old, with a fit slim body, Sonaram lives a life yet defined by physical toil and natural hardship. He recollected times from his youth when there were no roads and before sunrise he set-off to walk the 50 odd kilometres to Bikaner town with produce of 25 kilos and returned in the evening with provisions of equal weight.

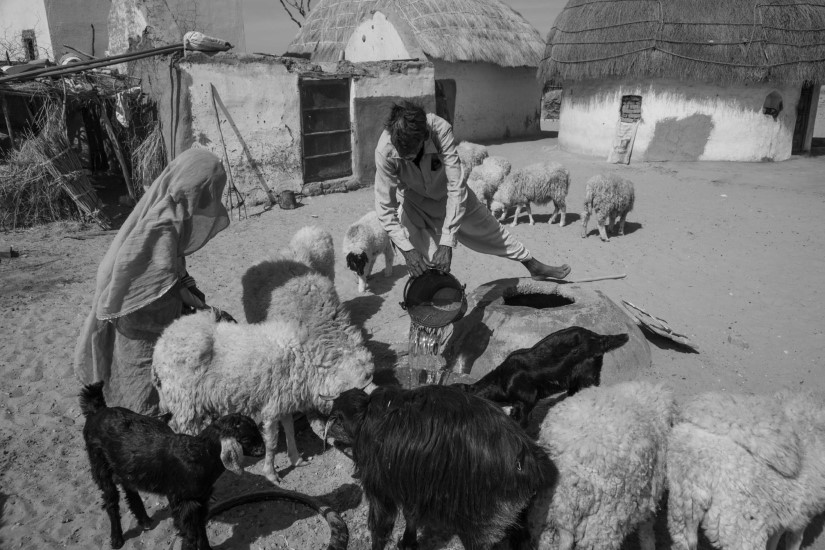

There is much more to write about the multi-faceted skills of Sonaram Meghwal. He constructs his own home, with the roof of dried Khemp grass sitting securely on a beautifully constructed frame of dried stems of the Ankh and Irni bushes, on walls made of mud. This home is cool in the summer when the temperature outside is 50 degrees Centigrade. He and his son Jethu have learnt to construct a cement room on their own. In addition, he is an expert at rearing animals and the uses of the plants and bushes of his ecology.

Post my second visit when I took their leave with much emotion, as their kind hospitality had irrigated my soul, Sonaram and Jethu shared the love in their simple hearts by gifting me many kilos of seeds of each of their crops. These men brought home to me that the bounty of nature is not to be copyrighted but is to be shared.

I trace my clan roots to the lands of Rajasthan a millennia back, and this was an amazing homecoming. I will be back in September to see the arid land turned green with Bajri, Gwar, Moth and Til and to wonder at the magical heritage of millions like Sonaram and my peasant ancestors who lived in harmony with Prakriti.

Sonaram Meghwal

Sonaram Meghwal

Sonaram’s Grandsons and their Camel

Sonaram’s Grandsons and their Camel

Precious Water

Sonaram's Compassion

Sonaram at work

Sonaram with Jethu and grandsons

Sonaram with Jethu and grandsons